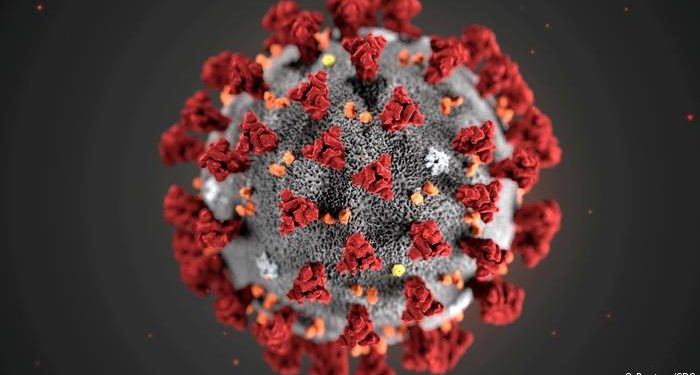

This time last year, concepts such as “lockdowns,” “mask mandates” and “social distancing” were unknown to most of us. Today they are part of our everyday language as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact all aspects of our lives. Through the following 12 charts and graphics, we try to quantify and provide an overview of our colleagues’ research in the face of a truly unprecedented crisis.

The New Poor

Over the past 12 months, the pandemic has harmed the poor and vulnerable the most, and it is threatening to push millions more into poverty. This year, after decades of steady progress in reducing the number of people living on less than $1.90/day, COVID-19 will usher in the first reversal in the fight against extreme poverty in a generation.

The latest analysis warns that COVID-19 has pushed an additional 88 million people into extreme poverty this year – and that figure is just a baseline. In a worst-case scenario, the figure could be as high as 115 million. The World Bank Group forecasts that the largest share of the “new poor” will be in South Asia, with Sub-Saharan Africa close behind.

According to the latest Poverty and Shared Prosperity report, “many of the new poor are likely to be engaged in informal services, construction, and manufacturing – the sectors in which economic activity is most affected by lockdowns and other mobility restrictions.”

Accelerated Economic Downturn

Those restrictions – enacted to control the spread of the virus, and thus alleviate pressure on strained and vulnerable health systems – have had an enormous impact on economic growth. The June edition of the Global Economic Prospects, put it plainly: “COVID-19 has triggered a global crisis like no other – a global health crisis that, in addition to an enormous human toll, is leading to the deepest global recession since the Second World War.” It forecast that the global economy as well as per capita incomes would shrink this year – pushing millions into extreme poverty.

Relieving the Debt Burden

This economic fallout is hampering countries’ ability to respond effectively to the pandemic’s health and economic effects. Even before the spread of COVID-19, almost half of all low-income countries were already in debt distress or at a high risk of it , leaving them with little fiscal room to help the poor and vulnerable who were hit hardest.

For this reason, in April, the World Bank and IMF called for the suspension of debt-service payments for the poorest countries to allow them to focus resources on fighting the pandemic. The Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) has enabled these countries to free-up billions of dollars for their COVID-19 response.

Yet, as the graph below illustrates, debt service outlays to bilateral creditors will impose a heavy burden for years to come, and quick action to reduce debt will be needed to avoid another lost decade.

As World Bank Group President David Malpass has said, “Debt service suspension is an important stopgap, but it is not enough.” He added that “many more steps are needed on debt relief,” including an expansion of DSSI while a more permanent solution can be developed.

Without more action on debt, a sustainable recovery could be stunted in many countries – along with a host of other development goals. As Global Economic Prospects noted, while many emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) were able to implement large-scale fiscal and monetary responses during the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis, today they are less prepared to weather a global downturn. The most vulnerable of them rely heavily on global trade, tourism, and remittances. The next edition of Global Economic Prospects, including updated forecasts, is due in early January.

Migrants Sending Less Money Home

Remittances – the money that migrants send to their home countries – are of special concern. Over previous decades, remittances have played an increasingly important role in alleviating poverty and sustaining growth. Just last year, these flows were on par with foreign direct investment and official development assistance (government-to-government aid).

But COVID-19 has spurred a dramatic reversal, with our latest forecasts finding that remittances will decline 14% by the end of 2021 – a slightly improved outlook compared with the earliest estimates during the pandemic, that should not belie the fact that these are historic declines. All regions can expect a drop, with Europe and Central Asia seeing the steepest fall. Associated with these declines, the number of international migrants is likely to fall in 2020 – for the first time in modern history – as new migration has slowed and return migration has increased.

These drops are cutting off a lifeline for many poor families in developing countries. Migrants’ remittances are crucial to households around the world , and as they decline, experts fear that poverty will rise, food insecurity will worsen, and households risk losing the means to afford services like healthcare.

Impact on Businesses and Jobs

The pandemic slowdown has deeply impacted businesses and jobs. Around the world, companies – especially micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the developing world – are under intense strain, with more than half either in arrears or likely to fall into arrears shortly. To understand the pressure that COVID-19 is having on firms’ performance as well as the adjustments they are having to make, the World Bank and partners have been conducting rapid COVID-19 Business Pulse Surveys in partnership with client governments.

These offer a glimmer of good news. Responses collected between May and August showed that many of these firms were retaining staff, hoping to keep them on board as they ride out the downturn. More than a third of companies have increased the use of digital technology to adapt to the crisis.

The same data warned, however, that the firms’ sales have dropped by half amid the crisis, forcing companies to reduce hours and wages, and most businesses – especially micro and small firms in low-income countries – are struggling to access public support.

Reduced family incomes – whether due to job loss, a stop in remittance payments, or a multitude of other COVID-19-related factors – will continue to put human capital at risk. With less money, families will be forced to make trade-offs and sacrifices that could harm health and learning outcomes for a generation.

The High Cost of Health Care

The pandemic has highlighted the need for effective, accessible and affordable health care. Even before the crisis began, people in developing countries paid over half-a-trillion dollars out-of-pocket for health care. This costly spending causes financial hardship for more than 900 million people and pushes nearly 90 million people into extreme poverty every year – a dynamic almost certainly exacerbated by the pandemic.

And health care is just one way that COVID-19 is affecting countries’ human capital. Even before the pandemic, the world faced a learning crisis, with 53% of children in low- and middle-income countries unable to read a basic text on completing primary school. Pandemic-led school closures intensify these risks.

Closing Classrooms

At the height of the COVID lockdown, more than 160 countries had mandated some form of school closures for at least 1.5 billion children and youth. Regular updates on global closures can be found here.

COVID-19’s effects on education could be felt for decades to come , not just causing a loss of learning in the short term, but also diminishing economic opportunities for this generation of students over the long term.

Due to learning losses and increases in dropout rates, this generation of students stand to lose an estimated $10 trillion in earnings, or almost 10 percent of global GDP, and countries will be driven even further off-track to achieving their Learning Poverty goals – potentially increasing its levels substantially to 63 percent, equivalent to an additional 72 million primary school aged children.

As economic conditions force families to make difficult decisions on household spending, concerns about student dropout rates have grown. Speaking on our Expert Answers video series, World Bank Global Director for Education Jaime Saavedra said he is particularly worried for students in secondary school and tertiary education.

Many in those demographics “will not come back to the system because this is going to be a huge economic shock, so families might not have resources or some [students] will have to resort to work,” he explained. Others who were previously on the brink of dropping out will be more likely to do so due to the pandemic, Saavedra said.

To mitigate these losses and try to sustain learning amid the crisis, countries are exploring options for remote learning – with mixed results. In many places, a key obstacle is a lack of high-quality, affordable broadband.

On the Development Podcast, we spoke to two Colombian mothers who live on opposite sides of the digital divide. We heard about their radically different experience of home-based education.

Internet Inequalities

Their experience is not unique: around the world, the pandemic and associated lockdowns are underscoring that digital connectivity is now a necessity. The internet is the gateway to many essential services, such as e-health platforms, digital cash transfers, and e-payment systems.

Unfortunately, access to digital infrastructure and connectivity remains severely limited in the world’s poorest countries, which are eligible for grants and concessional lending from the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA). While mobile coverage has expanded rapidly on a global level, IDA countries still lag far behind, with mobile internet penetration rates of 20.4 percent at the end of 2019, compared to 62.5 percent for other countries.

And while the pandemic demonstrates the need for greater connectivity, it could actually widen the digital divide, as private investments become constrained and public financing is diverted to urgent policy priorities like health and social protection.5

Gender Distinctions

And COVID-19 also poses a serious threat to other development “divides.” Notably, gender gaps could widen during and after the pandemic. This could reverse women’s and girls’ decades-long gains in human capital, economic empowerment, and voice and agency.

At the beginning of the year the Women, Business and the Law report noted considerable progress in women’s economic opportunity over the past 50 years. For example, in 1970, just two countries had laws mandating equal renumeration for work of equal value. As the chart below shows, that situation has significantly changed in 50 years. But even today more than two thirds of economies could still improve legislation affecting women’s pay.

Of course, equal pay is just one aspect of gender equality. Across multiple indicators, the pandemic is exacerbating risks for women and threatening hard-fought-for gains. As this crises has unfolded, women have lost their jobs at a faster rate than men , due to the fact that they are more likely to be employed in sectors hardest hit by lockdowns, such as tourism and retail. Additionally, women in low- and middle-income countries are more likely to be predominantly employed in informal jobs, which often means they lack access to social protection and other safety nets.

And the next generation? Girls in many countries may face increased expectations to take on care-related tasks that could affect their ability to stay engaged in education over the long term. Our partners at UNESCO have projected that 11 million girls might never return to their studies following the pandemic.

Millions More Without Meals

Beyond education, children – male and female – are also vulnerable to the global rise in food insecurity , affecting people in both urban and rural settings. Our World Development Indicators show that even before COVID-19 emerged, the number of people who were undernourished – an indicator that tracks how many people fail to access sufficient calories – was increasing, after decades of decline.

Like with so many other aspects of global development, COVID-19 stands to exacerbate this already worrying trend. The pandemic may add between 83 and 132 million people to the total number of undernourished in the world in 2020, according to a preliminary assessment by our partners at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). FAO’s data helps underpin the World Bank Group’s World Development Indicators.

Fragility, Conflict, Violence: Home to More and More Poor

In many places, food insecurity and COVID have compounded the impact of fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV) , which threatens a reversal of progress on development. In 2000, one out of five of the world’s extremely poor people lived in fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS). Since then, poverty has fallen steadily in other economies, but the number of poor people living in FCS continues to grow.

Today, around half the world’s poor reside in fragile and conflict-affected situations. In fact, poverty is becoming more concentrated in these places, which will be home to up to two-thirds of the world’s extremely poor people by 2030. COVID-19 is likely to further exacerbate this trend.

Seizing the Sustainability Opportunity

For FCV, food insecurity, and a number of other challenges, climate change is a “threat multiplier.” Even as the world focuses on the pandemic, climate shocks, natural disasters and ecosystem loss have not stopped. But how we respond to COVID-19 can help strengthen how we are able to handle future risks and shocks. As governments take urgent action and lay the foundations for their financial, economic, and social recovery, they have a unique opportunity to create economies that are more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient.

To support a resilient recovery, the World Bank Group will continue to make major investments that help countries integrate climate action into their development agendas.

The Group has steadily increased our climate financing: having committed $83 billion to climate-related investments over the last five years and exceeding our targets for each of the last three years. We will further boost support for countries to accelerate climate action and boost resilience to its mounting impacts. Amid COVID-19, this means looking at ways to align short-term objectives – like job creation and economic growth – with long-term goals like decarbonization, adaptation, and resilience to help our client countries shape a sustainable recovery.

Conclusion

The impact of COVID-19 has drawn numerous comparisons – some to the Global Financial crisis of 2007–2008, others to World War II, and more still to crises we know only from history books. While these may seem dramatic, the pandemic has had wide-ranging impact on nearly every aspect of development, like few crises before it.

The full scale of the pandemic will only be known in years to come, as we collect and analyze the data, adapt and evolve our financing to meet countries’ needs, and continue our work to end extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity. To pursue this mission effectively, we will remain a long-term partner to our client countries, providing the data, technical assistance, and financing that will be needed to navigate the global community out of this truly global crisis.