Bright Simon’s Take On Starlink’s Entry into Ghana

The standard claim is that low earth orbit (LEO) satellite broadband providers, like Starlink, will kill telcos and eventually rob governments of taxes. Like most things, there is always nuance. As the upcoming entry of Starlink into Ghana shows, incumbents and politicians don’t give in too easily.

Starlink is actually not Ghana’s first mass-market satellite internet entrant. It was OneWeb, an Eutelsat subsidiary seeking to challenge Starlink that nearly went bankrupt in the process until it was rescued by the UK govt and Airtel.

In 2022, it set up a gateway in Tema to be managed by top enterprise connectivity incumbent, Comsys, a favourite ISP for Ghana’s financial industry.

OneWeb’s rollout may have been slow but it gave ideas to the govt and regulatory bosses when the Starlink opportunity reared its head. They tried to convince the company, founded by maverick billionaire Elon Musk, to partner a lightweight state-owned entity called RuraCom to improve connectivity in rural areas but Starlink didn’t seem enthusiastic.

In the latest satellite internet licensing regime, the govt has made partnering with RuraCom and/or telecom incumbents a requirement for certain license categories.

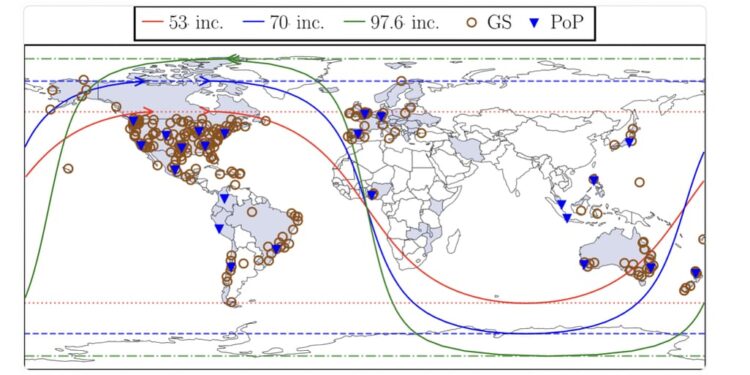

Starlink doesn’t even seem keen to establish a ground station or physical “point of presence” in Ghana yet. In Nigeria it has both, and is planning 4 more. In the UK it rents 3 gateways and is building 6 more. Just like in Ghana, the Elon Musk company hasn’t built any physical sites in Kenya and Mozambique. Traffic there is round-tripped as necessary to the nearest ground station in Nigeria.

In fact, the latest generation satellites in Starlink’s 6000-unit constellation even have laser links among them to reduce dependency on ground infrastructure as much as possible.

Unlike geostationary satellite applications, LEO systems like Starlink were designed from the outset to overcome the latency, bandwidth, and handover interval limitations of satellite internet provision more through sheer fleet size (Starlink aims to hit 12,000 satellites in the near future, and, according to Immarsat, there is an LEO project with a planned fleet-size of over 350,000 satellites). And connectivity among the satellites themselves.

Yet, a physical footprint cannot entirely be ignored when traffic surges. As recent research by a TUM-Edinburgh University team shows, as users multiply and traffic surges, ground infrastructure becomes critical else quality suffers, as has been the case in some parts of Latin America and the Philippines.

But traffic has to surge first. Business models, such as allowing users to rent expensive equipment instead of buying them outright, an experiment ongoing in Kenya, that will drive this surge for Starlink are yet to mature in Africa.

In Nigeria, dishes go for $275 ($350 in Kenya), and a monthly subscription costs ~$24. In Kenya, monthly rental rates are a mere ~$15 a month. Yet, disposable incomes being what they are, Starlink has struggled to hit 30,000 subscribers in Nigeria and is estimated to have a mere 6000 subscribers in Kenya. Analysts, however, believe that weak marketing partnerships are equally to blame.

Incumbents see an opportunity to engage. But partnering with mobile network operators hasn’t featured as strongly for Starlink as it has for other satellite operators.

MTN has tried to position very strongly as a strategic collaborator and has been working on pilot collaborations with multiple providers. In Rwanda, it is experimenting with the idea of Starlink facilitating enterprise connectivity and elsewhere it has mooted the concept of using it for backhaul operations.

Vodacom has a more intimate relationship with Starlink’s competitor, Amazon’s Project Kuiper.

OneWeb’s strategy seems increasingly more focused on this kind of reliance on incumbents. In Taiwan, it is Chunghwa Telecom’s fastest-growing bandwidth supplier. It also has agreements with Orange to provide backhauling in rural and remote locations across Africa, Europe and Latin America. Even geostationary players like Intelsat are hooking up with OneWeb to fill in latency gaps across their network.

Starlink too has signed backhauling deals with wholesalers like AMN and KDDI, but its strategy to own last-mile relations with consumers has never wavered. As also is the goal to minimise in-country costs.

So, at least for now, Ghana’s telecom chiefs may have to make do with just the $25,000 “earth station network” license and $6,000 application fees due from Starlink (unlike elsewhere, there is no requirement for a separate gateway license). There is also a requirement for it to pay 1% of annual revenue. But these sums are a far cry from the millions governments have got used to from telcos.

Any local use of frequency spectrum, however, would have to be licensed separately, providing yet another opening for politicians to push for “partnerships” with favoured telcos like AT and Ascend Digital.

It is a long road to anyone making any big bucks from Starlink’s entry into Ghana for sure, except maybe the lucky satellite dish distributor, the relatively obscure Galaxy Aerospace.