Ghana Still an Economic Mess After $7.3 Billion and 18th IMF Programme

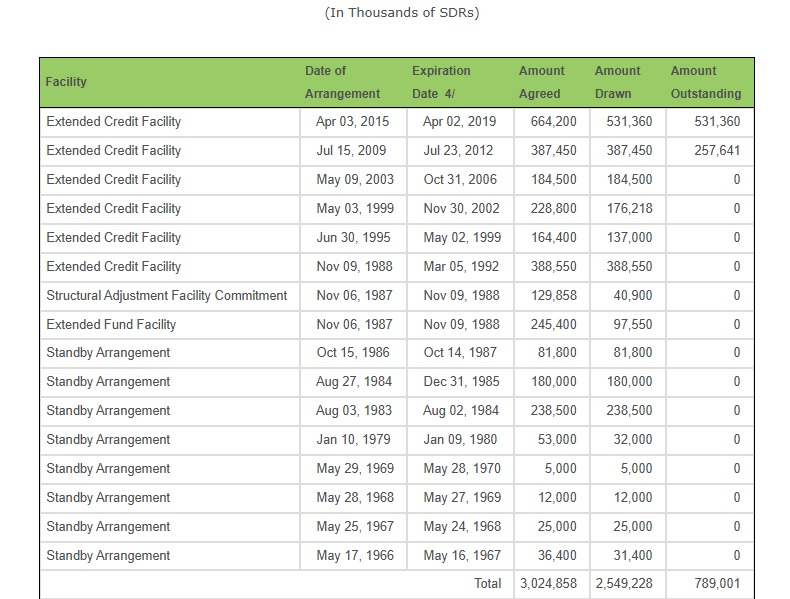

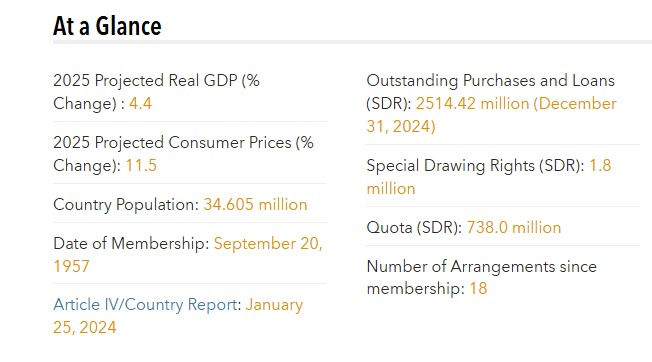

After securing an 18th programme with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and having been supported with some $7.3bn (SDR 5.52bn) since 1966, Ghana’s economy still finds itself in a deep mess and under significant financial strain.

This is evidenced by the high public debt stock which resulted in a default on debt obligations and necessitating a restructuring of the country’s external and domestic debts, with the country having only recently witnessed some signs of economic recovery in the form of receding inflation, seemingly stable exchange rate, declining interest rates on Government debt instruments, slightly reduced debt stock (occasioned by the debt relief from creditors), improved primary surplus, resumption of debt service payments following the default in 2022, among others.

Breakdown of Financial Assistance from IMF Since 1966

The $7.3bn (SDR 5.52bn) total financial assistance includes the $1bn (SDR 738m) Rapid Credit Facility secured during the Covid-19 pandemic and the current $3bn (SDR 2.24bn) Extended Credit Facility (ECF).

Since the country’s first request for financial assistance in 1966, Ghana has consistently been to the Bretton Wood Institution for help with the same economic challenges, indicating unwillingness to learn and undertake significant structural reforms that will ensure long-term stability and growth.

The recurring issues leading the country to the IMF include Debt unsustainability, Balance of payment challenges, High government expenditure, Domestic revenue underperformance, Economic mismanagement and Corruption.

Given the unwillingness of the managers of the economy to undertake significant structural reforms, it is very difficult not seeing Ghana go for a 19th or a 20th IMF programme.

Until these issues are intentionally resolved by managers of the economy, Ghana will continue to go to the IMF for financial and technical assistance.

There will be little to no surprise if Ghana should announce its intention to go for a 100th IMF programme in some decades to come.

The recently held National Economic Dialogue (NED) holds promise and is a step towards finding some solutions to the issues that have persistently plagued the economy and sent the country back to the IMF.

If indeed the incumbent Government and subsequent Governments are willing to continuously implement recommendations from the Economic Dialogue (including further recommendations from successive Economic Dialogues), then we are sure to make progress in breaking the cyclical dependence on the IMF.

However, if there is, on the part of the Government, reluctance in fully implementing the recommendations made at the Economic Dialogue and subsequent ones, then we just might be wasting our time and the taxpayers’ money in organising such events.

Ghana’s History with the IMF: A Timeline of Bailouts and Economic Challenges

May 1966 – May 1969: Ghana’s First IMF Bailout

Ghana turned to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the first time in 1966 following the overthrow of Prime Minister Dr Kwame Nkrumah by the National Liberation Council (NLC).

After the coup, the newly formed government invited the IMF and the World Bank to take the lead in managing the country’s economy. During this period, the IMF supervised the privatisation of state-owned enterprises in an effort to turn them into profitable institutions.

Between 1966 and 1969, Ghana relied on an IMF financial bailout under a ‘standby arrangement’ to stabilise its economy.

10 January 1979: A Return to the IMF

On 10 January 1979, Ghana sought IMF assistance again due to economic mismanagement, corruption, and a series of military coups that had hindered economic growth.

Prior to this, the military government, led by General Ignatius Kutu Acheampong, had attempted to promote self-sufficiency through the “Operation Feed Yourself” agricultural programme, launched in February 1972. However, by the time Acheampong’s regime ended in 1978, the programme had not been enough to sustain the economy.

The situation worsened after the 4 June 1979 coup led by Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings. Inflation soared to extreme levels, with economists stating that even toilet paper had more value than gold. The high inflation rate significantly increased the cost of essential goods such as soap and clothing, which had to be imported using foreign currency.

A group of 15 junior Air Force officers successfully overthrew the ruling government in 1979 and later handed power over to a civilian administration following elections. To address Ghana’s economic crisis, the new government entered another ‘standby arrangement’ with the IMF in 1979.

1980s: Hunger Crisis and 142% Inflation

Following the transition to civilian rule in 1979, J.J. Rawlings staged another coup on 31 December 1981, establishing himself as the chairman of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC).

IMF Bailouts in 1983, 1984, 1987, and 1988

Between 1981 and 1983, Ghana experienced severe drought and food shortages, leading to a hunger crisis. The country became reliant on food donations from international charities, and by 1983, it faced its worst economic downturn in modern history.

This prompted Rawlings and the PNDC to seek IMF assistance under a Structural Adjustment Programme. The Economic Recovery Programme (ERP), introduced as part of the IMF-backed reforms, transitioned Ghana from a state-controlled economy to a market-oriented system. These measures stabilised the economy and reduced inflation from 142% in 1983 to 10% by 1991.

Debt Cancellation: 1995, 1999, 2003, and 2009

From the mid-1990s, global financial institutions such as the IMF launched debt relief initiatives under the Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) programme.

Ghana benefitted from IMF support in 1995 and 1999 under the Fourth Republic during President J.J. Rawlings’ administration. However, in 2003, under President John Agyekum Kufuor, Ghana was formally classified as a HIPC country and returned to the IMF for debt relief.

After assuming office in 2001, President Kufuor sought HIPC debt relief in 2003, which reduced Ghana’s national debt from $66 billion in 2003 to $23 billion by 2006. Rather than directing all funds towards debt repayment, the IMF instructed Ghana to invest in critical sectors such as education, healthcare, and governance reforms.

2015: Power Crisis and IMF Bailout

Ghana’s energy crisis, popularly known as “dumsor,” led to economic challenges under President John Mahama’s administration. As a result, in 2015, the country once again sought IMF assistance.

The IMF approved a $918 million loan to Ghana to support economic reforms aimed at accelerating growth, creating jobs, and stabilising the Ghanaian cedi while ensuring social spending was protected. The Mahama administration justified the decision to seek IMF support, arguing that it was the best option to restore economic stability.

2022: Ghana’s Latest Return to the IMF

In 2022, Ghana once again sought assistance from the IMF under President Nana Akufo-Addo’s administration, a move that sparked public debate as the government had initially assured citizens that the country would not return to the IMF.

According to the government, the economic crisis was largely driven by external factors, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. By December 2022, inflation had reached 54%, one of the highest levels in Ghana’s history, having started the year at 13.9%. The rising inflation pushed up the cost of living, increasing food prices, goods, and essential services.

If since 1966 Ghana’s IMF support now is $7.3bn, and from 2017 to 2024 Ghana lost $20.1bn which ORAL (OPERATION RECOVER ALL LOOT) is targeting for Ghana’s development why would not we go for the $20.1bn and become self reliance. Let’s all rest the economy and Ghana for better future generations to come.

First step is a time line to stop importing food, make a significant investment in agriculture to reduce the cost of living. Introduce incentives for homeowners or landlords as a motivation for lowering rent for renters. Support for small businesses by granting low interest loans. Food processing industry for local and subregional markets

This platform will go a long way in galvanizing ideas and strategies to help the country

A positive step to heal the economy

Ab3kor) nsa; wine from the same palm tree. We are not getting anywhere with so called imagined democracy in a highly corrupt country. We need people to take bold sacrificial steps and I don’t see it in so called Africanstyle democracy. All in all one same cycle. On and on let’s think of it.