Ghana’s Sporting Triumphs and the Debate on a Proposed Sports Fund

The year 2025 has been a remarkable one for Ghanaian sports, marked by historic performances on the global stage. At the World Athletics Championships in Tokyo, Rose Amoanimaa Yeboah etched her name into the nation’s sporting history by becoming the first Ghanaian woman to qualify for the high jump final at a world championship. With a clearance of 1.92m, she not only reached the finals but also became the first Ghanaian athlete in two decades to achieve such a feat, following in the footsteps of Ignatius Gaisah and Margaret Simpson.

Equally inspiring was the performance of Ghana’s men’s 4x100m relay team, who set a new national record of 37.79 seconds in the heats before finishing fourth in the final with a time of 37.93 seconds. Though they narrowly missed out on a medal, their performance underscored Ghana’s growing prowess in sprint events. Beyond athletics, the University for Development Studies (UDS) football team made history by winning the 2025 FISU World University Games in Dalian, China, defeating Brazil’s Paulista University in the final to become the first African side to lift the trophy. On the football front, the Black Stars also boosted national pride with a resounding 5–0 victory over the Central African Republic, edging closer to qualification for the 2026 FIFA World Cup.

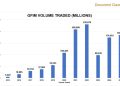

These achievements have reignited debates about the financing of sports in Ghana. Historically, government expenditure on sports has been heavily skewed toward football, often at the expense of other disciplines. The 2010, 2014, and 2022 FIFA World Cups alone cost the state GHS19 million, GHS9.6 million, and GHS14 million, respectively. Meanwhile, athletes in athletics, boxing, volleyball, and other disciplines frequently self-fund their participation or rely on external sponsorships, even though their victories bring glory to the nation. When government support is promised, bureaucratic delays often lock up sponsorships and rewards, leaving athletes frustrated.

In the wake of recent sporting successes, the government has announced the introduction of a Sports Fund Bill in Parliament. While the media has described it as a new “sports levy,” the Minister of Sports and Recreation, Hon. Kofi Adams, has insisted that it is a fund rather than a levy. Yet, as he himself admitted in interviews with Citi FM and JoyNews, no fund can be established without a levy of some kind. More troubling is the absence of clarity on how much the fund seeks to raise annually, or whether the finance minister will announce a levy in the upcoming budget.

The justification for the fund becomes even more complex when viewed against the backdrop of Ghana’s sports budget. In 2024, the Ministry of Youth and Sports was allocated GHS195,795,973. In 2025, this figure was slashed to GHS65,899,456—a staggering 66.4% cut. Even more concerning, the 2025 budget made no provision for capital expenditure (capex), compared to GHS50 million in 2024. The Sports development line item, long underfunded, received no appropriation in 2024 and 2025, though its allocations for employee compensation and goods and services in 2025 rose significantly from GHS18.5 million to GHS25.8 million and from GHS1.6 million to GHS6.19 million, respectively. Thus, while the overall budget shrank, the sports development line item saw a relative boost.

The proposed Sports Fund, however, raises critical questions. Its sources of revenue include percentages from sponsorship deals, athlete transfers, and even the financial gains of athletes themselves. This structure risks appearing as though the government is “reaping where it has not sown.” Can the state credibly claim to have invested sufficiently in the development of these athletes to justify taking a share of their earnings? What role does the government play in securing sponsorships for clubs or athletes? These are not merely rhetorical questions but fundamental issues of fairness and accountability.

The role of the National Sports Authority (NSA) also remains unclear in this new arrangement. Without a clearly defined mandate, the NSA risks being sidelined in the very process it was established to oversee. Moreover, Ghana’s history with special-purpose funds such as the NHIS, GETFund, MIIF, and the Cash Waterfall Mechanism shows that levies and earmarked funds often fail to deliver their intended outcomes. In 2025, the government had to draw from the tax refund account to cover education deficits and raise the Energy Sector Recovery Levy (ESRL) from GHS0.20 to GHS1 to keep the lights on. These precedents cast doubt on whether a Sports Fund would fare any better.

A more sustainable approach lies in medium to long-term planning and private sector engagement. As the Minister hinted, inviting corporate investment into sports development mirrors successful models in other jurisdictions. Sports is increasingly shifting from mere entertainment to an “experience economy,” where spectators are willing to pay for enhanced experiences. Multipurpose sports infrastructure could host athletics, volleyball, handball, hockey, and basketball alongside football, maximizing revenue streams. Examples of such abound, like the Wembley in England, Santiago Bernabeu in Spain, and the Mercedes Benz Arena in the US. Additionally, clubs could be encouraged to establish teams across multiple track and field disciplines, with the government’s role limited to facilitating investment and calling up athletes for national duty. Such reforms would not only reduce the financial burden on the state but also make the collection of any proposed percentages more transparent and justifiable.

Ghana’s recent sporting triumphs have shown what is possible when talent meets opportunity. But sustaining this momentum requires more than euphoric celebrations and ad hoc levies. It demands a coherent, medium to long-term sports development plan that balances government support with private sector investment, ensures fairness in resource mobilization, and prioritizes infrastructure and athlete development. When this is effectively done, Ghana’s athletes can continue to soar on the global stage, not in spite of the system, but because of it.