Inside Ghana’s Great Debt Restructuring: How a Nation Rewrote its Fiscal Future

Introduction

On 1st July 2022, trading volumes on Ghana’s financial markets were markedly subdued, reflecting a cautious investor sentiment ahead of the much-anticipated 2022 Mid-Year Budget Review. Market participants were particularly focused on assessing fiscal performance metrics, especially revenue realized from the newly implemented Electronic Transactions Levy (e-levy)—a policy tool introduced to broaden the tax base amid dwindling traditional revenue streams.

At the time, Ghana’s macroeconomic fundamentals were under significant strain. The Ghanaian cedi was experiencing sharp depreciation, headline inflation had surged into double digits, and both domestic and international financing conditions had tightened considerably. With limited fiscal space and rising debt servicing costs, the government faced a binary policy choice: either intensify domestic revenue mobilization to reduce dependence on debt financing or proactively seek external support through an IMF programme to anchor market expectations and restore macroeconomic stability.

During the first half of 2022, the government pursued an inward-looking strategy, banking on the e-levy and expenditure rationalization to stabilize the fiscal position. However, as fiscal and external imbalances deepened, investor confidence continued to deteriorate, leading to further pressure on the currency and sovereign risk spreads. Consequently, on 1st July 2022, the President mandated the then Minister for Finance to formally initiate discussions with the International Monetary Fund for a support programme.

This policy reversal underscored the severity of Ghana’s macroeconomic vulnerabilities and signaled a strategic shift toward multilateral support as a credible anchor for fiscal consolidation, debt sustainability, and external financing assurances. The decision marked a turning point in economic policy direction, with broad implications for fiscal strategy, monetary policy coordination, and investor engagement going forward.

THE TRANSITION FROM BURST TO BOOM (AND BACK TO BURST)

By the close of 2016, Ghana’s macroeconomic fundamentals had significantly deteriorated. Total public debt had escalated to GHS 122 billion (USD 29 billion), representing approximately 73% of GDP. The composition of the debt was split between external liabilities of GHS 69 billion (USD 16 billion) and domestic obligations of GHS 53 billion (USD 13 billion).

The Ghanaian cedi experienced a 9% depreciation against the US dollar, while year-end inflation stood at 15.4%. The Bank of Ghana maintained a tight monetary stance, with the policy rate at a restrictive 25.5%, reflecting high inflation expectations and risk premiums. Gross international reserves stood at USD 4.8 billion, equivalent to just 2.8 months of import cover—an indication of external vulnerability. On the fiscal front, the government recorded a fiscal deficit of 10.3% of GDP on a commitment basis, largely financed through increased public borrowing.

These adverse macroeconomic conditions were a key issue in the 2016 general elections, signaling a loss of market and public confidence.

Between 2017 and 2020, Ghana experienced a notable economic rebound. Inflation decelerated to 7.8% by August 2019, the lowest since September 2013, enabling the Bank of Ghana to ease monetary policy, lowering the benchmark rate to 14.5%. This easing cycle contributed to a decline in borrowing costs and supported real GDP growth, which reached 8.3% by year-end 2020.

However, this growth trajectory was underpinned by significant debt accumulation. By December 2020, public debt had expanded to GHS 291 billion (USD 50.8 billion), equivalent to 76% of GDP. Domestic debt amounted to GHS 150 billion (USD 30 billion), while external debt stood at GHS 141 billion (USD 28 billion), with a large share sourced from Eurobond issuances.

Ghana became increasingly reliant on international capital markets to finance its fiscal operations. The country executed successful Eurobond issuances in 2018 (USD 2 billion), 2019 (USD 3 billion), and 2020 (USD 3 billion), culminating in a further USD 3 billion raised in March 2021. These issuances were mostly oversubscribed, reflecting investor appetite for higher-yielding frontier market debt.

In addition to hard currency borrowing, Ghana attracted foreign portfolio inflows into its local currency bond market via the carry trade mechanism, where investors converted USD to cedis to capitalize on relatively higher interest rates. As of September 2021, non-resident investors held approximately 24% (GHS 35 billion) of Ghana’s domestic debt securities, increasing the country’s exposure to capital flow volatility and exchange rate risk.

External Shocks Exposed Ghana’s Underlying Fiscal Fragilities

Post-COVID-19, global investor sentiment turned risk-averse amid escalating geopolitical tensions, trade frictions, and macroeconomic uncertainty. The onset of the Russia-Ukraine war in February 2022 further exacerbated risk aversion, triggering a global flight to quality—a widespread capital reallocation from emerging and frontier markets into safe-haven assets such as U.S. Treasuries.

As a result, Ghana lost access to its traditional Eurobond financing window, which typically provided around USD 3 billion annually to support budget execution. With external markets effectively shut, Ghana’s structural fiscal weaknesses and heavy reliance on foreign financing were abruptly exposed, causing heightened anxiety among existing creditors.

To bridge financing gaps, the government pivoted towards domestic debt markets, though investor appetite proved insufficient. The 2022 Budget Statement, presented in November 2021, failed to signal any immediate intent to seek IMF assistance—contrary to expectations given Ghana’s 2014 precedent when it secured a USD 918 million Extended Credit Facility. Instead, the government opted for a self-financing strategy, aiming to ramp up domestic revenue through tax policy reforms, notably the controversial Electronic Transactions Levy (e-levy).

With no significant foreign exchange inflows, the Bank of Ghana (BoG) was compelled to draw down reserves to defend the cedi and honor maturing external obligations. On the local front, cedi-denominated debt was rolled over, but investor participation in auctions declined sharply, resulting in severe undersubscriptions. In response, the BoG assumed a quasi-fiscal role, monetizing portions of the deficit by covering maturing domestic securities.

By mid-year 2022, the fiscal pressures had intensified. The e-levy, initially projected to generate GHS 7 billion annually, had yielded only GHS 93 million in H1 2022, far below the half-year target of GHS 1.4 billion. Concurrently, revenue mobilization lagged: only GHS 37 billion was collected in the first half, against a target of GHS 43 billion. Meanwhile, expenditure targets (GHS 62 billion) were fully met, exacerbating the fiscal deficit.

To plug the financing gap of over GHS 28 billion, the BoG provided direct monetary financing to the tune of GHS 22 billion, with the balance sourced through domestic banks and multilateral project loans. The planned Eurobond issuance of USD 4.8 billion for 2022 was shelved due to lack of market access.

Amid deteriorating macroeconomic indicators, Ghana formally approached the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Following consultations led by IMF staff in early August 2022, it became evident that public debt, then approximately 88% of GDP, had become unsustainable. The emerging consensus was that comprehensive debt restructuring—both external and domestic—was the most viable path forward to restore macro-fiscal stability.

Phase I: The Path To Ghana’s Public Debt Restructuring

On 4th December 2022, following extensive deliberations amid intensifying fiscal pressures, the Minister of Finance officially declared a domestic debt default. The announcement marked a critical policy shift, as Ghana initiated a restructuring of approximately GHS 137 billion in domestic debt instruments. This debt stock included bonds issued by: The Republic of Ghana (Ministry of Finance), Energy Sector Levy Act (E.S.L.A.) Plc and Daakye Trust Plc

The restructuring framework proposed an exchange of existing debt instruments for a package of new bonds to be issued by the Republic. Concurrently, the government announced a moratorium on debt service payments for selected external debt obligations, as part of a broader strategy to stabilize the macro-fiscal environment and restore debt sustainability.

On 6th December 2022, Ghana formally launched the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP). The program outlined the terms of the voluntary debt swap but explicitly excluded: Treasury Bills (short-term instruments) and Debt instruments held by individuals (natural persons). These exclusions were intended to protect retail investors and preserve confidence in the short-term funding market.

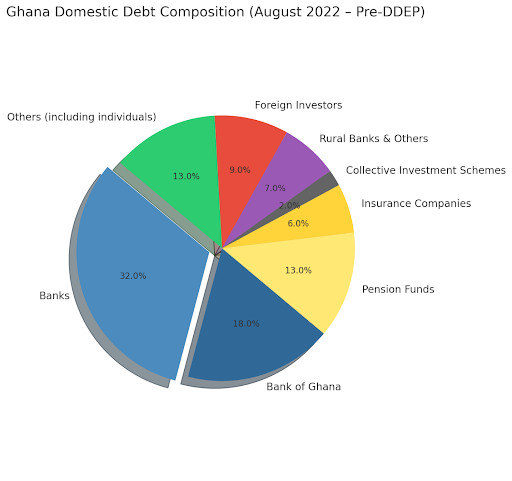

As of August 2022, Ghana’s total public debt stood at GHS 373 billion, with the composition of domestic debt showing a concentration of exposure to the banking sector, which held approximately 32% of the total. Recognizing the systemic importance of financial institutions and the need to maintain financial stability, the Ministry of Finance prioritized engagement with banks in the initial phase of the restructuring process.

Incentives And Reliefs: The “Carrots And Sticks” Of Ghana’s Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (Ddep)

On 7th December 2022, the Financial Stability Council (FSC)—an inter-agency body established in 2018 to monitor and mitigate systemic financial risks—outlined a set of supportive measures and regulatory accommodations to facilitate the successful implementation of the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP).

The Carrot: Ghana Financial Stability Fund (GFSF)

To incentivize full participation from financial institutions, the Ministry of Finance, with technical and financial support from the World Bank, established the Ghana Financial Stability Fund (GFSF), with an initial envelope of GHS 15 billion. This fund was specifically designed to:

- Provide liquidity backstops to eligible financial institutions severely impacted by the debt exchange.

- Support capital adequacy restoration, particularly for banks and other financial intermediaries whose bond portfolios were significantly impaired under the DDEP.

Institutions eligible for support under the GFSF included: Banks and Special Deposit-Taking Institutions (SDIs), Pension Funds, Collective Investment Schemes (CIS), Fund Managers and Broker/Dealers and Insurance Companies

Access to the fund was contingent on full participation in the DDEP, creating a strong incentive mechanism for broad-based compliance.

Regulatory Forbearance: Temporary Relief Measures

To mitigate the immediate balance sheet stress and prevent financial contagion, regulators issued temporary forbearance measures relating to:

- Capital adequacy requirements

- Liquidity ratios and solvency thresholds

- Suspension of new prudential rules that would have exacerbated sectoral vulnerabilities during the transition period

Each financial regulator (e.g., BoG, SEC, NIC, NPRA) issued sector-specific guidance to clarify how affected entities could operationalize these relaxations while maintaining regulatory oversight.

Accounting Treatment: Harmonized Guidance on New Bonds

Given the significant implications of the DDEP on financial reporting, the FSC collaborated with external auditors and the Institute of Chartered Accountants Ghana (ICAG) to provide clarity on the treatment of the “New Bonds.” ICAG issued a Discussion Paper detailing acceptable accounting approaches, helping institutions address concerns about impairment, valuation, and income recognition under the new instruments.

IMF Agreement: A Conditional Lifeline

On 13th December 2022, the Ministry of Finance and the IMF issued a joint press statement confirming a Staff-Level Agreement (SLA) for a USD 3 billion Extended Credit Facility (ECF). The SLA outlined policy conditionalities and prior actions, notably: (a) Completion of the DDEP as a pre-condition for IMF Executive Board approval and (b) Fiscal consolidation, structural reforms, and enhanced revenue mobilization targets

In essence, the domestic leg of the debt restructuring became a gateway requirement for unlocking external financial support and restoring macroeconomic credibility.

Timeline And Execution Of The Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP)

The rollout of Ghana’s Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP) was marked by multiple deadline extensions and revised terms, reflecting the government’s efforts to negotiate consensus among diverse investor groups and secure high participation.

Chronology of Key Milestones:

19th December 2022: Original deadline for voluntary participation in the DDEP.

24th December 2022: The Ministry of Finance (MoF) announced the first extension to 30th December 2022, citing the need to accommodate feedback from stakeholders.

30th December 2022: A second extension was announced, revising key terms of the exchange and pushing the deadline to 16th January 2023. The revision aimed to improve the attractiveness of the offer, especially for pension funds and financial institutions.

31st January 2023: A third and final DDEP offer was published, accompanied by a further deadline extension to 7th February 2023. This final offer consolidated prior revisions and was widely considered the last window for voluntary participation.

Settlement and Participation:

On 21st February 2023, the New Bonds under the DDEP were officially settled.

The programme achieved an 85% participation rate, which, although below 100%, was considered sufficiently high to proceed with subsequent stages of debt restructuring and meet the IMF Staff-Level Agreement benchmarks.

IMF Approves Ghana’s USD 3 Billion Bailout

Following the successful completion of the first phase of the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP), the IMF Executive Board, on 17th May 2023, approved a USD 3 billion Extended Credit Facility (ECF) for Ghana. The approval was granted under the IMF’s “Lending in Arrears” policy, signaling the Fund’s confidence in Ghana’s reform agenda—even though the comprehensive debt restructuring had not yet been finalized.

This IMF approval was a major turning point, unlocking external financing and restoring market confidence. It also paved the way for the second phase of Ghana’s domestic debt restructuring process.

Phase Ii: Deepening The Domestic Debt Operation

The government subsequently rolled out targeted debt exchange programmes to restructure special categories of domestic liabilities, including:

USD-Denominated Domestic Bonds

📅 Launch Date: 14th July 2023

💼 Target: Reprofiling of locally issued U.S. dollar-denominated bonds

✅ Outcome (29th August 2023): Achieved 92% participation rate

Cocoa Bills Exchange Programme

📅 Launch Date: 14th July 2023 (concurrent with USD bonds)

🎯 Purpose: Improve liquidity and reduce rollover risks in short-term commodity financing instruments

✅ Outcome: Reached a 97% participation rate by 29th August 2023

🛡️ Pension Funds Alternative Offer

📅 Launch Date: 31st July 2023

🏛️ Context: Designed as a compromise after pension funds were initially exempted from the main DDEP

✅ Outcome: Concluded with 95% participation rate by 29th August 2023

Bank of Ghana Agreement & Completion of Domestic Restructuring

A separate agreement was reached with the Bank of Ghana (BoG), marking the conclusion of Ghana’s holistic domestic debt restructuring exercise.

Cumulative Impact:

- GHS 203 billion in total domestic debt exchanged

- GHS 61 billion in estimated debt service savings for the year 2023 alone

Next Stop: The External Debt Restructuring

After successfully completing the domestic piece of the debt restructuring, Ghana turned its focus on the external piece. Of the total USD 29 billion external debt, only the IMF and the World Bank – owed USD 1.71 billion and USD 4.75 billion respectively – were fully exempted.

Below is the External Debt Mix as of August 2022;

| External Debt Mix (as of August 2022) | USD ‘ billion | |

|---|---|---|

| Multilateral | IMF | 1.71 |

| World Bank | 4.75 | |

| African Development Bank | 1.19 | |

| Other Multilaterals | 0.40 | |

| Bilateral | Paris Club (mostly European countries) | 2.87 |

| Non-Paris Club (mostly China and India) | 2.57 | |

| Private Creditors | Eurobonds | 13.10 |

| Commercial Creditors | 2.27 | |

| Total | 28.87 | |

The Two-Pronged Approach To Ghana’s External Debt Restructuring

Following progress on the domestic front, Ghana turned its attention to the external component of its public debt, estimated at USD 29 billion. The restructuring strategy targeted both bilateral and commercial creditors, in line with the IMF’s debt sustainability requirements and under the principle of Comparability of Treatment.

Breakdown of External Debt (Pre-Restructuring)

USD 2.87 billion – Owed to Paris Club bilateral lenders

USD 2.57 billion – Owed to Non-Paris Club sovereign creditors

USD 13.10 billion – Eurobond obligations

USD 2.27 billion – Commercial and other external creditors

Step 1: The G20 Common Framework & Bilateral Negotiations

12th December 2022: Ghana officially requested debt treatment under the G20 Common Framework, aimed at negotiating terms with both Paris Club and Non-Paris Club creditors (collectively termed as the Official Bilateral Creditors).

April 2023: Formation of the Official Creditor Committee (OCC) comprising bilateral lenders. Simultaneously, private creditors formed two ad-hoc committees: One for regional bondholders and another for international bondholders

Discussions commenced across all creditor platforms, guided by the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA) and consistent treatment principles.

Step 2: Private Creditor Engagement & Eurobond Restructuring

24th June 2024: Ghana reached an Agreement in Principle with both the regional bondholders (holding ~15%) and international bondholders (~40%).

The agreement involved a nominal haircut of approximately USD 4.7 billion

📉 Cash flow relief of USD 4.4 billion was expected over the IMF program period

📅 11th October 2024: Ghana successfully settled the Eurobond Exchange Offer, achieving:

📆 Reduction in average maturity from 18 years to 6 years

💰 Coupon reduction from an average of 10% to ~3%

This marked a significant step in alleviating debt service pressures and restoring fiscal space.

Step 3: Finalizing Bilateral Terms

29th January 2025: Ghana signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with its Official Bilateral Creditors, formalizing the terms agreed with the OCC in June 2024.

🔄 Remaining Outstanding

As of June 2025, Ghana continues to negotiate with commercial external creditors to finalize the last leg of its holistic USD 63 billion debt restructuring.

Lessons Learned: Why Ghana’s Debt Exchange Succeeded In Record Time

Ghana’s swift and largely successful debt restructuring offers key takeaways for other sovereigns facing similar fiscal distress. Despite the scale and complexity of the operation, Ghana executed a holistic restructuring of both domestic and external debt components in under three years — a rare feat in sovereign finance. The following factors contributed to the success:

- ✅ Early Backing from the IMF Boosted Credibility and Confidence

Immediately following the announcement of debt restructuring plans, the IMF and Ghana’s Ministry of Finance issued a joint statement confirming a USD 3 billion Extended Credit Facility (ECF) under the ‘Lending in Arrears’ framework. This reassured creditors and markets that:

- The restructuring would be anchored on a comprehensive macroeconomic reform agenda

- Ghana had a lender-of-last-resort committed to restoring fiscal discipline and rebuilding reserves

- A baseline policy credibility was in place to mitigate uncertainty and contagion risks

- This IMF support served as a seal of approval, catalyzing investor confidence and expediting stakeholder cooperation.

- ⚖️ Robust Legal and Financial Due Diligence Prevented Contention

Ghana’s approach was grounded in rigorous legal and financial risk assessment:

The Financial Stability Council — comprising key regulatory bodies including the Bank of Ghana and the Securities and Exchange Commission — conducted comprehensive stress tests to quantify the systemic impact of the debt operation on the financial sector. Based on these findings, regulators granted temporary capital and liquidity forbearances, while the Ghana Financial Stability Fund (GFSF) was launched with GHS 15 billion in liquidity to cushion distressed participants (particularly banks).

Critically, Ghana avoided legal coercion. Legal advice from the Attorney-General’s Department strongly advised against unilaterally introducing Collective Action Clauses (CACs) through legislation or executive action, deeming such a move likely unconstitutional and potentially litigious. Instead, Ghana structured the exchange as voluntary, ensuring CACs were only embedded in the new bonds, and accepted by bondholders as part of the terms of exchange. This move minimized legal resistance and helped ensure a smoother, litigation-free restructuring process.

- 📣 Transparent Communication and Fair Burden Sharing Reinforced Cooperation

Ghana maintained a clear and consistent narrative that restructuring was an essential pillar of broader macroeconomic reform, not a stand-alone event. This narrative was bolstered by three core communication strategies:

- Holistic treatment of all creditor classes, signaling no preferential deals or carve-outs — thereby fostering a sense of equitable burden-sharing

- Ongoing engagement with all stakeholder groups including pension funds, foreign investors, commercial banks, and individual bondholders

- Clear articulation of the expected outcomes, including restored fiscal sustainability and long-term macroeconomic stability

As a result, the domestic debt exchange achieved 85% participation, and the follow-up exchanges for foreign currency bonds, pension funds, and cocoa bills recorded over 90% uptake. Losses across creditor groups averaged 30%, but the perceived fairness and transparency of the process helped maintain investor goodwill and minimize political and social backlash.

The Way Forward: Sustaining Debt Sustainability Post-Restructuring

Ghana’s comprehensive debt restructuring has provided temporary liquidity relief, stabilized macroeconomic sentiment, and restored short-term market confidence. However, the operation has not fundamentally eliminated debt overhang risks. The country now faces the challenge of ensuring long-term fiscal sustainability and avoiding a return to debt distress.

Under the new structure, Ghana must service an average of USD 1 billion annually on its restructured Eurobonds until 2037. On the domestic front, the maturity profile of local currency bonds remains front-loaded, with over GHS 100 billion in debt service obligations due in 2027–2028. These structural vulnerabilities underscore the urgency for disciplined fiscal policy and proactive debt management.

Key Strategic Priorities for Ghana’s Post-Restructuring Fiscal Path

- Reduce Dependence on External Financing

Reliance on foreign portfolio flows and Eurobond issuances to support the cedi and fund budgetary gaps has proven risky and volatile. Ghana must prioritize:

- Deepening domestic capital markets to mobilize long-term local funding

- Enhancing tax revenue mobilization to reduce the fiscal gap

- Building reserves to support external shocks and reduce BoP vulnerabilities

- Maintain a Strict No Central Bank Financing Rule

The Bank of Ghana’s direct financing of fiscal deficits prior to the restructuring contributed to inflation, currency depreciation, and macroeconomic instability. Going forward, zero central bank financing must be enshrined in both policy and law, consistent with IMF programme benchmarks.

- Implement Active and Preemptive Debt Management Strategies

Ghana’s Debt Management Office (DMO) must adopt more forward-looking tools to manage rollover and concentration risks:

- Sinking funds for the systematic retirement of maturing debt

- Opportunistic debt buybacks when market conditions allow, to reduce future liabilities

- Debt swaps or exchanges to smooth out maturity cliffs and extend the yield curve

- Institutionalize Fiscal Discipline

Restoring fiscal space requires robust efforts to address:

- Public sector inefficiencies and leakages

- Corruption and procurement-related waste

- Streamlining expenditure and improving value-for-money assessments

This includes tighter fiscal rules, improved PFM systems, and accountability mechanisms.

- Diversify Export Base to Mitigate Commodity Dependence

Currently, over 85% of Ghana’s FX earnings come from gold, cocoa, and oil. This exposes the economy to global commodity price shocks. Ghana should focus on:

- Developing non-traditional exports (e.g., services, agriculture, manufacturing)

- Encouraging value addition in commodity sectors

- Strengthening FX buffers and risk-hedging instruments

- Preserve the Yield Curve Established Through the Debt Exchange

The DDEP successfully consolidated a fragmented bond landscape of over 100 instruments into a manageable yield curve. This should now serve as:

- A benchmark for future issuances (via reopening rather than new securities)

- A pricing reference for other domestic financial instruments

- A signal of market discipline and predictability in issuance strategy

- Timely and Proactive Engagement with the IMF

Ghana has had multiple IMF programmes in the last two decades, but often delayed engagement until macroeconomic conditions deteriorated significantly. To avoid future crises:

- IMF support should be sought proactively as a preventive mechanism

- Future engagements should focus on structural reforms, not just balance-of-payments relief

- Exit strategies should be clearly defined to avoid dependency cycles

This publication was authored by Prince Oppong and Norman Adu Bamfo, volunteer contributors at Treasury Hub GH, bringing a combined two decades of experience in financial markets—spanning foreign exchange, interest rates, and balance sheet management. It is intended solely for educational purposes, to document Ghana’s historic debt restructuring process and offer forward-looking insights for policy and market participants.

Credits: Bloomberg LLP, Ministry of Finance Ghana, Bank of Ghana and the International Monetary Fund