MTN’s Shadow Banking Empire – Is Ghana’s Financial Stability at Risk?

- The MTN Question – Corporate Power or Financial Risk?

When mobile money (MoMo) launched in Ghana, it was hailed as a triumph of innovation, one that would democratise access to finance and bring the informal majority into the formal economy. At the forefront of this financial revolution was MTN Ghana, the country’s largest telecom provider, whose yellow kiosks and app interfaces now underpin everyday transactions from Wa to Accra.

But nearly two decades later, MTN’s financial footprint has morphed from a transactional tool to a quasi-banking empire, and its dominance has begun to raise uncomfortable questions. With mobile wallet float deposits now estimated to be nearly three times the size of the entire Ghanaian banking sector’s deposit base, experts are warning that Ghana’s economy may be sitting on a dangerously oversized financial ecosystem.

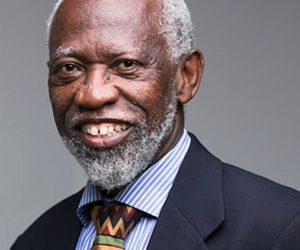

The ballroom at the Movenpick Ambassador Hotel was filled with applause on the evening of April 5, 2025, as Ghana’s finest financial institutions gathered to celebrate excellence. But the evening’s keynote address, delivered by Emeritus Professor Stephen Adei, economist, public administrator, and Companion of the Order of the Volta, cut through the ceremony with surgical clarity.

In a bold, unsparing speech, Prof. Adei took aim at what he described as one of the most urgent but overlooked threats to Ghana’s financial system: the unchecked dominance of MTN’s mobile money operations, which he likened to a shadow financial empire operating beyond the central bank’s radar. “MTN is today probably the biggest corporate financial institution in Ghana, even if many citizens are not aware of it,” he began. “If left unchecked, MTN will hold the nation to ransom one day. Mark my words.”

It was a thunderclap of a statement, and it came with data, analysis, and deep institutional insight. In a country where mobile money has become as common as cash itself, Prof. Adei’s speech cast a spotlight on the mounting risks behind this convenience—and questioned why regulators have not yet acted decisively.

The Rise of MoMo—and Its Hidden Empire

MTN’s mobile money platform currently serves over 15 million active users in Ghana, with daily transaction volumes exceeding hundreds of millions of cedis. In a country where less than 50% of adults have access to traditional bank accounts, the appeal is undeniable.

But the unintended consequence of that growth is that MTN has become, effectively, Ghana’s largest financial institution, without ever registering as one. MoMo wallet balances, or “float deposits”, are meant to be held by licensed partner banks in trust. However, the operational control and liquidity flow remain with MTN, and most of these funds exist in a regulatory grey zone.

The Scale of the Problem: “Three Times the Banks”

At the centre of Adei’s concern is the sheer size of MTN’s financial footprint. Ghana’s largest telecom provider, through its mobile money (MoMo) platform, now controls float deposits that are nearly three times the total deposit base of the entire banking sector, as earlier reported in this article. “These are float deposits that sit largely outside the formal banking system,” he warned. “They are not subject to the regulatory supervision that banks face, yet they influence liquidity, interest rates, and even the exchange rate.”

Indeed, Prof. Adei’s revelations confirm what many insiders have whispered for years: that MTN has become a de facto bank, controlling critical liquidity flows, but without any of the capital adequacy requirements, lending regulations, or systemic safeguards that the rest of the financial sector must abide by.

Imagine a bank controlling a third of national liquidity with no regulatory compliance obligations. That, we at NorvanReports believe is essentially the position MTN is in.

The Currency Drain: MoMo and the Forex Crisis

One of the most alarming dimensions of MTN’s operations, Prof. Adei noted, lies in its role in Ghana’s remittance ecosystem. Beyond liquidity concerns, MTN’s remittance partnerships have further magnified its influence on Ghana’s foreign exchange reserves. The company partners with 11 fintech firms to process inbound remittances, one of the country’s largest sources of forex.

However, these inflows are paid out locally in Ghanaian cedis, while the actual foreign currency is retained offshore or repatriated, bypassing the Bank of Ghana’s reserves entirely, allegedly. Some financial experts have alleged contributing significantly to a cumulative FX loss running into billions of dollars between 2019 and 2024.”

In a country which grappled with dollar shortages, a volatile currency, and low foreign reserves, this revelation lands with particular weight. By monetising remittance flows in cedis while the USD equivalent remains offshore, MTN’s model, Prof. Adei argues, is quietly undermining Ghana’s forex stability. “We are losing control over one of the most stable sources of forex inflow,” he lamented. “And we’re doing it in plain sight.”

Shadow Lending and the Threat of Credit Contagion

MTN has also ventured into credit markets, partnering with some regulated institutions to offer small, collateral-free loans to millions of subscribers. While the company brands it as financial inclusion, critics argue it is a parallel credit market that operates without any of the tight oversight obligations imposed on banks, microfinance institutions, or savings and loan companies.

Borrowers take loans directly from their mobile wallets, often at high interest rates, with automated deductions structured into MoMo transactions. Defaults are managed algorithmically, but there is no clear reporting of non-performing loans (NPLs), creditworthiness metrics, or compliance with central bank lending caps. “There is zero transparency on credit exposure,” noted a banking consultant. “If there were a major disruption to MTN’s parent operations or platform failure, the cascading effect on consumer liquidity could trigger a mini-crisis in consumption and retail lending.”

A Broader Governance Crisis: “The State Must Wake Up”

In his address, Prof. Adei placed the MTN dilemma within a broader indictment of Ghana’s governance and regulatory culture. “The nation rises and falls on the quality of its governance framework,” he said. “And yet, when it comes to institutions like MTN, our regulatory response has been timid, reactive, and far too late.”

He pointed to other sectors, such as mining, where the state has demanded equity stakes and greater transparency. In the same spirit, he proposed government acquisition of a 40% stake in MTN Ghana, echoing the model he supports for resource-based sectors. “A company that can shape exchange rate trends, undermine fiscal tools, and operate like a bank without a licence must not be left to grow unchecked,” he emphasised.

What makes the situation more precarious is the absence of crisis planning. MTN’s operations are integrated into the daily lives of millions, used for salaries, school fees, taxes, and even government social interventions.

Yet, in the event of:

- A market exit

- An MTN Group-wide insolvency

- A cybersecurity breach

- Or a government-declared regulatory freeze

There is no resolution mechanism akin to those required of licensed banks. In short, MTN has become “too big to ignore” without being “too regulated to fail”.

Policy Vacuum or Policy Capture?

Observers are also questioning why regulators and policymakers have been reluctant to act. “Part of the problem is regulatory lag,” says a governance researcher at the University of Ghana. “But the bigger issue is what we call policy capture. MTN is a major taxpayer, employer, and public-facing brand. It’s difficult for politicians to push for strict reforms without facing backlash or lobbying pressure.”

Indeed, Prof. Adei alluded to this uncomfortable truth in his speech, noting that even respected members of the economic elite serve on MTN Ghana’s board. “I know I’m treading on dangerous ground,” he said, “but silence is complicity.”

Policy Roadmap: The Adei Doctrine

As a former board member of Baroda Bank and chair of two major mutual funds, Prof. Adei’s critique comes not from alarmism but from experience. He offered concrete policy proposals during his remarks:

- Track and Regulate All Remittance Flows: “All foreign exchange must be accounted for by the Bank of Ghana. Full repatriation of forex from fintech partners must be non-negotiable.”

- Subject MTN to Prudential Regulation: MTN’s lending activities must fall under the purview of the Financial Stability Council, with borrower protection and responsible lending standards enforced. “MTN must be classified as a systemically important financial institution, with float deposits included in monetary policy frameworks.”

- Audit the Cloud Infrastructure: “We must understand the operational risks of digital wallet systems, particularly in cloud architecture that’s not domiciled locally.”

- Restructure Float Holdings via the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP): There is growing support for requiring MTN to invest a significant portion of its float deposits in Domestic Debt Exchange Programme (DDEP) bonds, holding them to maturity. In exchange, banks would receive upfront cash injections to improve sector liquidity and restore credit to the real economy.

“If we can’t control the float, we can at least direct its deployment,” said a senior advisor at the Ministry of Finance. “That’s the essence of fiscal sovereignty.”

Silence, Power, and Policy Capture

In a particularly revealing moment, the maverick Prof. Adei acknowledged the political sensitivity of his critique: “The Chairman of the first Ghana’s Economic Forum under the government of John Mahama is also MTN Ghana’s Board Chair, and my mentor, Ishmael Yamson. I know I risk a serious reprimand for speaking out. But silence would be complicity.”

This admission underscores the political complexity around MTN. As a top taxpayer, employer, and ubiquitous brand, MTN wields immense soft power. But Adei’s remarks were a call to break that silence and reassert the primacy of regulation in a functional democracy.

The Cost of Inaction

For Prof. Adei, this is not a debate about a telecom company; it is about the credibility of Ghana’s economic management. “Without action, we risk currency instability, fiscal slippage, and a liquidity crunch in the banking sector. Investors will lose confidence. And Ghana will lose control of its own financial future.”

His final call was not for panic but for bold leadership: “Resetting the agenda must have as its centrepiece resolving the debt crisis—and helping the corporate finance sector feel secure to lend long term. That begins with recognising where unchecked power lies.”

For now, the system holds, but the margin for error is narrowing. “We must remember that innovation without regulation is a ticking time bomb,” Prof. Adei concluded. “Let’s not wait for the explosion.”

Mostly because of banking hall attitudes the people prefer the digital banking industry. Government regulation is lacking because of corruption within the the regulatiry agencies.

Urgent reforms is long overdue. Thanjs