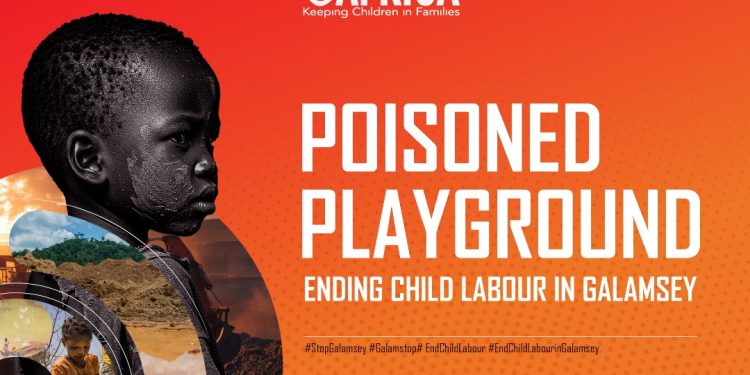

‘Poisoned Playgrounds’: National NGO Forum Demands Urgent Action to End Child Labour in Galamsey

The National NGO Forum, led by child-focused non-profit OAfrica, has intensified calls for urgent national action to end child labour in illegal small-scale mining, widely known as galamsey.

Held at the University of Ghana, the forum brought together stakeholders from Ghana’s health, education, environment and social protection sectors. The event, which marked the World Day Against Trafficking in Persons, focused on exposing the effects of child exploitation in mining communities and called for decisive steps to reverse what organisers described as a worsening national crisis.

Project Manager at OAfrica, Francis Anipah, described the situation as a moral failure that requires an emergency national response.

“We call them illegal mining sites, but to the children trapped in them, they are poisoned playgrounds. These children are not just skipping school. They are breathing in mercury vapours, carrying heavy rocks and facing abuse – all in a desperate attempt to survive. This is not just about mining. This is a child rights emergency, and Ghana must act,” he said.

One of the most disturbing testimonies presented at the forum came from Professor Anthony Kwame Enimil, a Consultant Paediatrician and Infectious Disease Specialist. He narrated the case of a four-year-old boy from Wassa Ayiem who passed metallic beads in his stool. An X-ray revealed mercury pellets in the child’s intestines and rectum.

“The child had unknowingly drunk mercury stored in a plastic bottle at home, commonly used by his parents for gold extraction. Exposure to mercury in children can cause long-term damage to the brain, kidneys and lungs. What is more worrying is that this is not an isolated case. Thousands of children in galamsey areas are at risk of similar or worse exposure, and many have no access to health care,” he explained.

According to a 2022 UNICEF report cited at the forum, an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 children in Ghana are involved in mining-related activities. Many of these children are aged between 12 and 17, but others are as young as five. The tasks they perform include digging deep mining pits, crushing rocks with rudimentary tools and handling mercury and cyanide without any protective gear.

These activities violate international conventions to which Ghana is a signatory, including the International Labour Organisation (ILO) Convention 182 on the Worst Forms of Child Labour and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Speakers at the forum also drew a direct link between illegal mining and environmental destruction.

Deputy Director at A Rocha Ghana, Daryl Bosu, presented a detailed analysis of how galamsey is rapidly destroying forests, water bodies and farmlands, which in turn endangers the health and wellbeing of children.

“In 2023 alone, Ghana lost over 110,000 hectares of forest. That’s equivalent to nearly 200,000 football fields. This destruction released 76.3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide. Our rivers like the Ankobra, Pra, and Offin have become unusable. Communities are forced to rely on polluted water sources, which has led to increased disease outbreaks and food insecurity. Even COCOBOD had to refund a $250 million African Development Bank loan because irrigation for cocoa production was no longer viable in some areas. This is not just an environmental issue – it is a public health and child protection crisis.” he said.

The forum also highlighted the gendered nature of the problem. An officer at the Gender and International Affairs Unit of the Minerals Commission, Abigail Ziame, revealed how girls in mining communities bear a disproportionate burden.

She said, “Many girls are forced to drop out of school to care for younger siblings or assist with unpaid household chores. Others are trafficked to mining sites under false pretenses and end up in exploitative situations. They face early pregnancies, sexual violence, and trauma that stays with them for life,”

According to the Minerals Commission’s internal research, more than 5,600 children are known to be directly involved in mining, though this figure is likely underreported due to the hidden nature of the problem.

Although Ghana’s legal framework is clear on the matter, enforcement remains a significant challenge. The country’s 1992 Constitution, the Children’s Act (Act 560), the Labour Act (Act 651), the Human Trafficking Act (Act 694), and the Minerals and Mining Act (Act 703) all prohibit child labour, especially in hazardous environments such as mining.

However, forum participants expressed frustration that these laws are not being enforced effectively. They attributed the failure to limited resources, lack of training for local law enforcement and a general absence of political will.

The forum concluded with a strong call for a coordinated national response. Stakeholders recommended that the government strictly enforce child protection and mining laws, particularly in districts known for illegal mining activities. They called on the Ministry of Education to invest in interventions that improve school access and retention – such as school feeding programmes, safe transportation and targeted community engagement. The Ministry of Health was urged to expand mercury screening and treatment services for children exposed to harmful chemicals in mining zones. There were also calls for the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources to scale up community-based monitoring and promote the adoption of safer gold processing technologies like the Lantern Retort developed by the University of Mines and Technology (UMaT).

Stakeholders further called on social welfare officers, the police and local leaders to adopt child-sensitive interventions and collaborate more closely, backed by proper training and adequate funding.

As Ghana marks the World Day Against Trafficking in Persons, the 2025 National NGO Forum leaves no room for doubt: the country cannot continue to trade its children’s safety for gold. What is needed now is not another report, but bold, coordinated action – because no child should ever call a mine pit home.