Proposed U.S. Tax On Remittances: Cost of Administering Tax on Remittances Likely to Exceed Revenue Collection, But Tax Will Hurt Millions Worldwide

On top of worries about deportations and the return of migrants, a proposed tax on remittances sent by unauthorized migrants – originally 5%, currently 3.5% – has rightly caused a lot of concern among remittance-recipient countries.

As we head into the 4th Forum on Financing for Development in Seville in just over a month from now, remittances have emerged as the largest source of external financing for low- and middle-income countries. At over $700 billion in 2024, remittances are now larger than the sum of all private investment flows and official aid. This year, while major sources of foreign exchange –export revenue, foreign investment, official aid, and private philanthropy – are likely to decline due to tariff wars and geopolitics.

Remittances are unlikely to decline, and will likely become even more of a financial lifeline in developing countries. In many countries – notably poorer, smaller and fragile countries – remittances exceed 20% of national income. After years of debates and discussions, therefore, in the negotiations leading to Sustainable Development Goals, a target was introduced to reduce remittance costs to 3% by 2030.

A tax of 3.5% will render the SDG indicator 7.c.1 impossible to achieve. Understandably the proposed tax on remittances is cause for worry.

Even more worrisome, if the US introduces a tax on remittances, many other countries are likely to follow suit. Here is, therefore, a note to point out why a tax on remittances is not a great idea. This note complements an earlier note on why taxing inward remittances is difficult to implement and on the broader topic of taxing migrants.

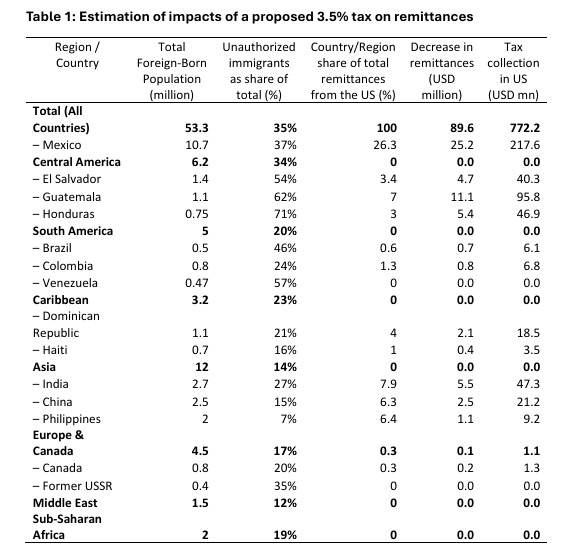

A 3.5% tax on outward remittances sent by unauthorized migrants in the US is likely to raise less than $1 billion in revenue. Indeed, the additional paperwork – collecting IDs, paying the tax, maintaining records – imposed on remittance transfer providers (RTPs) will incur costs and reduce their profits, which would in turn reduce their tax payments (table 1).

According to official data, outward remittances amounted to about $84.3 billion in 2024. Using estimates of unauthorized migrants in the US from the Pew Research Center, the taxable amount of remittances would be around $29 billion. However, migrants would choose ways to reduce the cost of sending money in various ways: they would hand carry, send money with friends traveling home, through courier services or bus drivers and airplane pilots, find friends in the US who’d arrange to pay local currency to beneficiaries in the recipient countries, use hawala-hundi channels, and cryptocurrencies. In the calculation reported in Table 1, a quarter of flows are assumed to be diverted to such informal channels.

Remittances are cost elastic; a tax would increase the costs of sending money and reduce the amount sent. Some studies estimate that a 1% increase in remittance cost would reduce remittances by 0.09%. Such a reduction in remittance volumes in response to a 3.5% tax is likely to be small, less than $90 million. Together with the taxes paid, the total reduction in remittance flows to developing countries is likely to be only $772 million – an amount that will not be visible in the tax collection spreadsheet of the World’s largest multi-trillion dollar economy.

The likely loss to developing countries, however, will be disproportionately larger. Even so, the reduction in remittances is likely to be negligible.

Will the proposed tax deter unauthorized immigration to the United States? Will it encourage unauthorized migrants to return home? Doing a minimum-wage job in the United States earns a person over $24,000 per year, some four times to 30 times more than in a developing country. Such a person sends home to family back home between $1,800 to $4,800 per year. A 3.5% tax is unlikely to discourage remittances. After all the main motivation for migration – migrants trying to cross oceans and rivers and mountains – is to send money home to help helpless family members.

This note reflects the author’s personal views, in response to many requests for comments received recently from governments and money transfer industry participants.