“Independent Councils Won’t Fix Ghana’s Debt Addiction—Only the Constitution Can”

- Why Dr. Atuahene says real fiscal discipline demands constitutional backing

In the face of Ghana’s persistent debt overhang, it is tempting and almost expected that the government will reach into the toolbox of technocratic solutions.

At the centre of the government’s reform package, as outlined by Finance Minister Dr. Cassiel Ato Forson during a recent post-budget parliamentary workshop, is the proposed Independent Fiscal Council. The minister stated that the body would enforce fiscal discipline and act as a check on government borrowing.

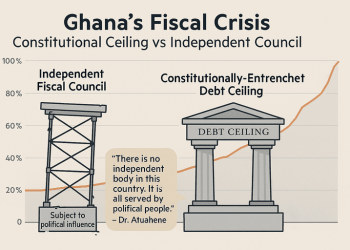

But in Ghana’s current political context, the idea of an “independent” fiscal body is, at best, aspirational, many have suggested, and, at worst, a distraction if it has no constitutional backing.

However, a Banking and Financial Analyst, Dr Richmond Atuahene, pointed out to the Constitutional Review Committee that no institution in Ghana, however well-intentioned or well-staffed, is immune from political influence when he appeared before the Reconstituted Constitutional Review Committee. The notion that such a council could effectively restrain fiscal profligacy without constitutional backing, he says, is “painfully not right”.

Dr. Atuahene must be right to be sceptical. Ghana’s fiscal management landscape is littered with well-crafted laws that have been either suspended or ignored when they become politically inconvenient. The Fiscal Responsibility Act, once touted as a game changer for budget credibility, was cast aside in 2020. The Public Financial Management Act, despite its comprehensive framework, has not prevented off-budget expenditures or creative accounting. The pattern is clear: secondary legislation is too easily trumped by political expediency.

If Ghana is serious about building long-term resilience in its public finances, it must move beyond what Dr. Atuahene called the “political theatre” of independent councils. Instead, the country needs a constitutionally entrenched debt ceiling, one that cannot be amended by simple parliamentary majority and which places hard limits on borrowing across political cycles, Dr Atuahene argued strongly at the committee meeting on Monday 7th March, 2025.

Such ceilings are not uncommon. The European Union’s Maastricht criteria include a strict debt-to-GDP cap. The U.S. Congress is regularly embroiled in political showdowns over the federal debt limit not because it is ideal but because it forces uncomfortable fiscal conversations.

Ghana needs a similarly binding anchor: a constitutional provision that not only sets the limit but also requires clear and transparent justification for any deviations, subject to independent judicial or parliamentary review.

The country’s debt has surged to levels that prompted a painful domestic debt exchange, and now the country finds itself in an IMF programme that demands structural reform. Yet, unless the foundational weakness, the lack of enforceable fiscal rules, is addressed, any reprieve will be temporary.

Ghana’s political leaders must resist the urge to perform reform. True fiscal discipline must be codified where it cannot be casually overridden: in the constitution. The time for symbolic fixes has passed. The political courage to bind the hands of future governments is what the moment demands.