Cocoa’s dizzying volatility is spilling into the coffee market

Cocoa and coffee have become intertwined this year, with extreme weather and shortages fueling rallies of both commodities that test the limits of traders.

Just like cocoa, the coffee market is facing severe shortages. And, like cocoa, coffee production is concentrated in two countries. More importantly, many major traders deal in both commodities, so soaring cocoa prices are squeezing those market players for cash and forcing them out of coffee trading.

The linkage is important because it helps explain in part why prices for coffee soared — and how a cash crunch is shutting traders out of the market. Cocoa’s latest impacts on coffee may end up being limited thanks to its differences from the chocolate-making ingredient.

The coffee trade might have been “contaminated” by a wave of speculative buyers betting prices would rise after the troubles in cocoa, said Carlos Costa, head of sales for Hedgepoint Global Markets LLC.

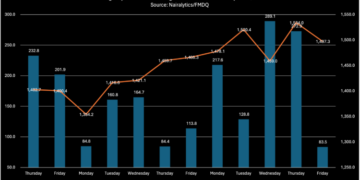

Futures of robusta coffee rallied more than 70% over the six months through April to hit the highest price in more than four decades. Cocoa prices have more than doubled this year to a record last month.

The cocoa rally has had a “psychological effect” on coffee, spurring comparisons between the commodities, said Andre Acosta, a director at financial firm Marex Group Plc. Both cocoa and robusta futures may have drawn “significant margin calls” as they rose, forcing traders to lift hedges or trade options to protect their positions. Margins for companies sourcing both commodities might be “hurting,” he added.

Aggregate open interest — or the number of outstanding contracts — fell in both cocoa and robusta markets as prices rose, spurring volatility. But fundamentally, factors like the concentration of cocoa production in West Africa makes it “much more challenging in the long term than coffee,” Acosta said.

The world’s supply of coffee and cocoa comes from a handful of countries. Vietnam and Brazil account for more than half of global coffee bean exports — and Vietnam has suffered from severe drought. Cocoa’s two biggest producers are West Africa’s Ghana and Ivory Coast, where production shortfalls are causing unprecedented volatility and record-high prices.

“Cocoa’s large concentration in just two countries led to the problems we are seeing now, and we can’t let the same thing happen to coffee,” said Vanúsia Nogueira, executive director of the International Coffee Organization. While the situation of coffee markets may be less extreme, she said the commodity is “following along the same lines” of cocoa.

While supply concerns are already pushing up coffee prices, market watchers say the bean used in breakfast beverages is poised to fare much better than cocoa.

Coffee growers are replacing older plants with new and more productive ones at a set pace each year, supporting yields and fending off disease, said Thiago Cazarini, who runs a brokerage firm in Brazil’s coffee belt. The incentive for farmers to invest in coffee is “significantly higher,” he said, as producers can immediately benefit from the rise in market prices.

That’s one big difference from cocoa, since prices in Ivory Coast and Ghana are fixed by governments. Even with the current cocoa rally, farmers are paid far less than market levels, and decades of underinvestment has made it difficult for the growers to replace aging trees or pay for pesticides and fertilizer that could boost yields.

Coffee’s Strength

Coffee is likely to fare better than cocoa once European Union regulation aimed at preventing deforestation takes effect at the end of the year. That’s because coffee intake is more global than chocolate, which is concentrated in Europe, said Megan Fisher, a researcher at Capital Economics. Europe imports nearly 60% of the world’s cocoa beans and accounts for more than three-quarters of global chocolate sales.

Cocoa is also a difficult ingredient to replace while coffee’s two bean varieties — arabica and robusta — make substitutions easier. When prices of the lower-quality robusta rise, companies can create coffee blends with cheaper versions of the premium arabica bean instead. That higher demand for arabica has been reflected in recent market moves, with New York futures gaining as much as 20% before trimming gains this year even with expectations of surplus supply this year.

Brazil — the world’s top coffee grower — has “consistently improved” arabica production in recent years, Rabobank analyst Guilherme Morya said in an interview. Coffee addicts can rejoice in the fact that there are beans to turn to, even though they may be of a different origin, price and variety. Still, an intensifying market concentration with Brazil increasing its share of global coffee shipments raises concerns.

A failure to diversify sourcing origins “can end up fundamentally changing the industry model and potentially breaking the trade,” said Trishul Mandana of major coffee trader Volcafe. “I believe we are witnessing this today in cocoa and the coffee industry has a lot to learn from these events.”