How African cities can learn from each other about building climate resilience

The climate is changing at an astronomical rate and the impact of this can be seen everywhere. Imagine stepping outside your apartment for an early morning jog, only to be greeted by a thick brown dust that makes breathing unpleasant.

The seasonal harmattan wind brings another round of degraded air quality that causes respiratory issues for many. Each year, it’s a stark reminder about how climate shocks are altering the everyday lives of millions of Africans, especially those living in cities.

Local perception is that this fury of nature is worsening as erratic and extreme weather events like scorching heatwaves, fierce storms or long droughts disrupt our livelihoods.

Yet in the midst of these challenges is the visible spirit of African resilience. More necessary than ever, communities must come closer together, share goals, knowledge and ideas, and co-create innovative solutions to the problems that plague us all.

Here’s how some cities in Africa have responded to climate shocks and what others can learn from their experiences and better understand how to build a future of shared climate resilience and prosperity.

Effects of climate shocks are close to home

In 2019, just after Cyclone Idai struck in Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe, Durban – the third-most populous city in South Africa – was hit by torrential rains.

“More than 1.7 million people were affected by both extreme weather events, with damages and losses amounting to over $3 billion,” noted Mark Lundell, World Bank Country Director for part of the region at the time. Homes were swept away, crops destroyed and lives lost.

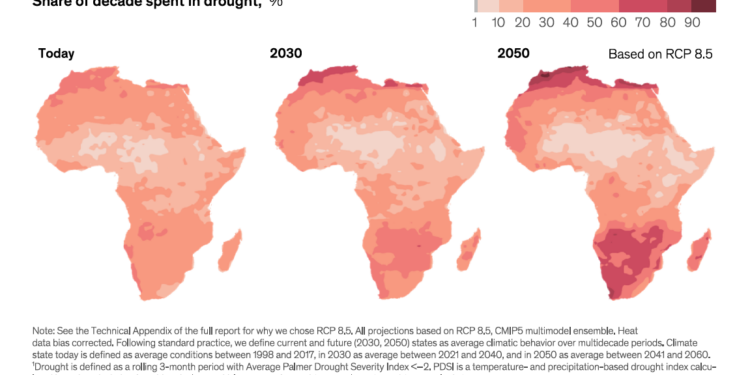

Expected evolution of drought differs by region in Africa, with the most affected areas in the north and south.Image: McKinsey & Company

Then in 2020, Kenya’s capital and largest city, Nairobi experienced its driest year on record. This drought led to widespread water shortages, with residents queuing for hours for water whilst struggling with dry taps occasioned by rationing programmes.

Even crops are not spared ahead of an impending hunger crisis. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) has warned that millions across East Africa will face severe food insecurity due to these extreme weather events.

How one city shifted towards green infrastructure

One thing that the South African city of Durban realized in the wake of Cyclone Idai is that its traditional, concrete-heavy flood management system cannot save it from raging storm intensity. So the city embarked on a transformative shift towards “green infrastructure”, mirroring nature’s process of flood mitigation system.

Durban’s response to the situation offers valuable insight for other coastal cities facing, or likely to face, similar threats. Here’s how it sought to beat the storm:

1. Durban identified and prioritized the restoration of degraded wetlands within the city limits. Wetlands typically act as natural sponges, absorbing and storing excess rainwater runoff and reducing peak flood levels, especially during heavy storms. A 2021 study conducted by the University of KwaZulu-Natal found that restored wetlands in Durban reduced flood risk by an estimated 20%, highlighting their efficacy in addressing flooding issues in cities.

2. Realizing that mangroves act as natural barriers, absorbing wave energy and reducing coastal erosion caused by intensified storms, Durban intensified the strategic planting of trees and mangroves that are uniquely adapted to saltwater environments. This idea was arguably derived from having a clear understanding of the city terrain. Research by Wetlands International Africa indicates that mangrove restoration projects in Durban have not only reduced erosion, but also created a habitat for fish and bird populations to thrive.

3. In a final effort to beat the storm, Durban incorporated bioswales – shallow, landscaped channels – into its urban landscape. These vegetated channels do not only capture but also filter stormwater runoff, reducing its volume and velocity before it enters drainage systems. The 2022 Durban Green Corridor report highlights how the implementation of bioswales in several neighbourhoods resulted in a significant decline in localized flooding events.

How a grassroots movement tackled water shortages

Kenyan capital Nairobi’s record driest year record in 2022 exposed the vulnerability of the city’s water supply system, which is heavily reliant on unpredictable rainfall patterns.

A unique grassroots movement emerged to promote rainwater harvesting as a viable alternative. At the core of their solution is a distributed network of organizations – including nongovernmental organizations and community-based organizations – that spearheaded the rainwater harvesting movement in Nairobi.

Their approach is to inform and encourage residents, businesses and schools to install rainwater tanks or reservoir to capture and store rainwater during the wet season. And they did not stop there; they conducted public awareness and sensitization campaigns to educate the people about the benefits of rainwater harvesting, as well as guide them on installing and maintaining the tanks.

The GROOTS Kenya Trust offers microloans or subsidies to assist households, particularly in low-income communities, in purchasing and installing rainwater tanks. The key to achieving significant impact is that the initiative it is largely community-driven; groups take charge of their development by defining the problem, conceptualizing the solutions, designing and implementing interventions, and tracking change.

Building climate resilience through adaptive cities

Durban and Nairobi’s actions and responses to their prevailing climate shocks offer a strong message and a pathway for other African cities facing the ever-changing challenges of a warming world.

These cities did not just react; they self-reflected and created solutions that are deeply-rooted in their very being and visibly addressed their specific vulnerabilities. Important considerations and best practices include:

1. African cities boast a wealth of traditional knowledge and practices passed down and refined over generations. Why not revisit these practices and see if they can be adapted to address contemporary challenges? Perhaps drought-resistant crops cultivated by our ancestors decades or even centuries ago can inform strategies to attain food security today and in the future.

2. Citizen participation is not just a ‘nice to have’. It is the lifeblood of a resilient city. Local communities must be empowered – through resources and skills – to take ownership and become active participants in nation building.

3. No city is an island. Cities must come together to learn from each other’s successes and failures. Creating and strengthening platforms for knowledge-sharing will enable African cities to exchange best practices and adapt them to their specific contexts.

Conclusively, building resilience against the impact of climate change is about creating a city that can adapt, bounce back and even thrive in the face of unforeseen shocks, stresses and challenges.

African cities can rewrite the narrative of vulnerability and become the beacon of resilience and prosperity by coming together, embracing Indigenous knowledge, empowering and supporting citizens, and fostering collaboration.