Subsidy: Labour threats foster value destruction in Nigeria

In response to the government’s plan to remove petrol subsidy since 1977, Nigeria’s labour groups shut down the economy in protests, but have never protested the government’s inability to fix the refineries despite spending billions in maintenance and paying a fortune to idle workers, or even rampant corruption in the sector.

Rather, labour unions including the Nigerian Labour Congress (NLC) and the Trade Union Congress (TUC) and their affiliates are enabling value destruction in the economy and leaving the workers they are supposedly agitating for even poorer, while unwittingly enabling corruption by some government officials and oil marketers, BusinessDay analysis shows.

The argument of choice against removing subsidies is that it would inflict hardship on workers. Yet, a new report by Lagos-based geopolitical research firm, SBM Intelligence, found that despite retaining subsidies, transport costs and petrol prices rose by over 283 percent in five years.

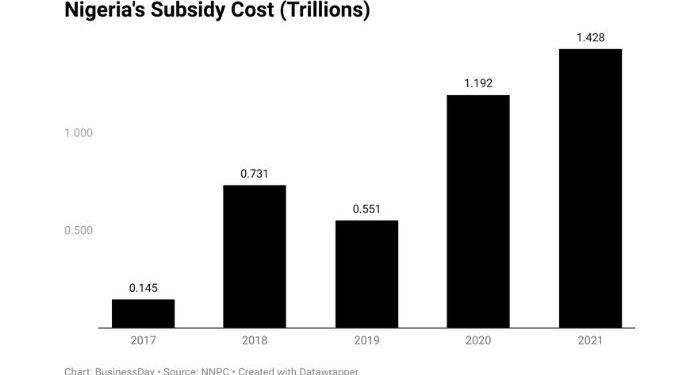

However, within this period subsidy payments rose through the roof. Between 2017 and 2018, the cost of petrol subsidy increased by 405 percent from N144.53 billion to N730.86 billion.

In 2020, the government incurred N1.192 trillion in subsidies, more than double the cost for 2019. By 2021, this has risen to N1.43 trillion, a stunning rise of 890 percent. This year, the NNPC is asking for N3 trillion from the government to fund petrol subsidies.

Nigeria’s labour groups are not galvanising workers to ask the government why an economy with the world’s poorest people with over 23 million people without jobs is burning N3 trillion to subsidise petrol.

To put this in the right context, figures from the budget office state that as at November 2021, Nigeria’s aggregate revenue was N5.51 trillion. The NNPC is asking for 54 percent of Nigeria’s income last year to pay petrol subsidy. Labour has not brought down the roof.

Labour unions often argue that removing subsidies would have a detrimental effect on food and other things. However, even with subsidies, food inflation is currently at 17.3 percent, transport costs have risen as well as the cost of everything else from real estate to clothing.

Ten years after the NLC, TUC and civil society groups squelched former President Goodluck Jonathan’s plan to remove petrol subsidy, the fortunes of the Nigerian workers have only worsened.

Within this period, double-digit inflation has eroded savings, 13 million children are out of school, hundreds of doctors and nurses have fled Nigeria and roads have morphed into death traps.

But Labour has won the Nigerian worker cheap petrol – it doesn’t matter that he cannot now afford a 20-year-old used Camry from Detroit.

Under the guise of petrol subsidy, marketers perpetrated a heist on the country in 2011, robbing the country over N2 trillion in fake waivers for petrol they did not import.

Labour’s agitations provide cover for this national heist, as daily consumption figures of petrol have surged from barely 35 million litres in 2015 to anywhere between 60 and 90 million litres in 2022, as the sale of illicit Nigerian petrol oils black markets and distorts price mechanisms across West Africa.

At $0.4 a litre, Nigeria’s petrol is the cheapest in West Africa helping to drive black-market petrol sales from Cameroon to Sudan. According to estimates by analysts, over 30 million litres of Nigeria’s petrol are smuggled daily across the country’s borders that are as porous as a spaghetti strainer.

Petrol price publication by the Nigerian Bureau of Statistics has consistently shown petrol price is not uniform across but the labour unions are not fighting for the rights of Nigerians in rural Agbor and Mbaise.

Joe Ajero, deputy national president, NLC, did not provide answers to BusinessDay inquiries on these matters.

Following the issuance of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) ‘Selected Issues Report,’ which said petrol subsidy had a significant negative impact on Nigeria’s fiscal position, raising the overall fiscal deficit by around 1 percentage point of GDP in 2021, labour is talking tough.

The IMF recommends that Nigeria should simultaneously implement market-based pricing recommended by the Petroleum Industry Act, (with mitigating measures to protect the poor, including cash transfers), and the medium-term conversion plan from petroleum to natural gas vehicles (NGVs).

“These two are not replaceable, but rather, complementary,” the IMF said. “Fuel subsidy is regressive and generates a large fiscal burden and distortion of resource allocation.”

Labour disagrees. Ajaero in a media report said the IMF does not mean well for the masses and workers.

Labour unions have maintained that the refineries must be fixed to achieve a low retail price of petrol. But there is no empirical evidence that petrol prices will suddenly become cheaper on account of local refining. The cost of crude is inching towards $100 per barrel and inefficiencies in the sector will yet add some unexpected costs.

Labour unions say it is a shame that Africa’s biggest oil producer cannot refine its crude. But shame is not a factor for economic planning.

Several countries import things they have no competitive advantage in producing. For example, the United States imports Avocado from Mexico because it is produced cheaper and local production cannot meet national demand.

“Nigeria’s five refineries, with a combined installed refining capacity of 445,000bpd, cannot meet national fuel demand of 42.57 million litres of petrol in 2020,” said Ese Osamwonyi, senior oil and gas analyst at SBM Intelligence.

Osamwonyi said fixing existing refineries and associated infrastructure will not negate fuel subsidy payments under the current regime

“Both issues are sufficiently decoupled from each other that the link labour often seeks to draw between them does not exist economically,” Osamwonyi said.

The analyst further said challenges with the cost of operating a refinery in light of existing business infrastructural challenges including technical issues as well as vandalism of its pipeline infrastructure, will likely mean that the refineries themselves if fully revamped will attract some form of government subsidy in order to remain operational.

The Nigerian government has a poor record of managing refineries (or anything for that matter). By refusing to rely on data and sound economic principles in its agitation, the Nigerian Labour movement, which thinks itself a veritable check against misrule, has become its greatest enabler.

Analysis shows that a labour’s insistence that the Federal Government fix 40-year-old refineries at the cost of billions of dollars without any guarantee they would be managed any better, while several refinery projects stall due to lack of market price for petrol, even as illegal refiners ruin the environment and Nigerians suffer the destruction of their cars due to dirty petrol imported by NNPC before it can allow deregulation, is either actively sabotaging the nation or being complicit in the sector’s woes.

Bismark Rewane, CEO, Financial Derivatives Company, said the Dangote Refinery may not translate to cheaper prices as it would only save shipping costs. However, the country’s poor road networks, insecurity challenges could cancel out much of these gains anyway.

Labour unions blocked late President Umar Yar’dua’s plan to privatise the refineries in 2007. Many cite the compromised power sector privatisation of 2013 as an example of the evil of privatisation, yet the Eleme Petrochemicals and the telecoms sector privatisation exercises show that a credible process will produce good results.