A Research Paper by Dr. Richmond Atuahene (Banking Consultant) and Isaac Kofi Agyei (Data & Research Analyst)

First, here are the research findings:

RESEARCH FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS ON THE IMPACT OF BANK OF GHANA’S NEW CASH RESERVE RATIOS FOR COMMERCIAL BANKS

A great area of concern about the Bank of Ghana’s decision to set higher cash reserve requirements for commercial banks is that these higher ratios could affect the credit to the private sector. According to the BoG March 2024 MPC report, private sector credit growth by banks remained sluggish, with February 2024 showing a 5.1 percent increase compared to 29.5 percent growth in February 2023.

Conversely, investments by banks in Government of Ghana (GOG) and Bank of Ghana (BOG) instruments surged to GHS 53.6 billion, marking a 67.6 percent year-on-year rise, contrasting with a 36.9 percent increase in the corresponding period of 2023. Adjusted for inflation, private sector credit saw a decline of 14.7 percent, compared to a 15.3 percent contraction in February 2023. BoG attributed the sluggishness to the risk aversion of banks as asset quality weakened over the period.

Declined was not the making of banks but harsh economic conditions of higher inflation, persistent depreciation of the Cedi, myriad of higher and nuisance taxes and higher utilities and energy crises as well as higher policy rates which made the banks adopt lazy banking by investing in the money market instruments. Government after the Domestic Exchange Programme (DDEP) in 2023, Treasury bill instruments became a lucrative business for banks as rates rose above 30 percent.

The Bank of Ghana’s policy on the New Cash Reserve Ratios has a notable flaw in that it overlooks the GHS 50.6 billion worth of government bonds that were previously restructured during DDEP. These bonds constitute part of the commercial banks’ total deposits of GHC 224 billion, with customers’ deposits being utilized for purchasing these government bonds.

Consequently, the Bank of Ghana should have considered the GHS 50.6 billion of bonds that were restructured before implementing the new, higher Cash Reserve Ratios; otherwise, it amounts to double accounting. The government bonds have a final maturity period in 2031, and many bank boards and management teams are concerned that this new directive could lead to a depletion of their resources soon as many banks may not be liquid enough to operate.

The central question remains: How did the Bank of Ghana establish the new Cash Reserve Ratio without factoring in the restructured bonds held by commercial banks, primarily funded by depositors’ money? Besides Bawumia (2010) argued that the high level of reserve requirements was a legacy of high fiscal deficits so why the heavy dependence on monetary policy to solve a problem deeply rooted in fiscal recklessness?

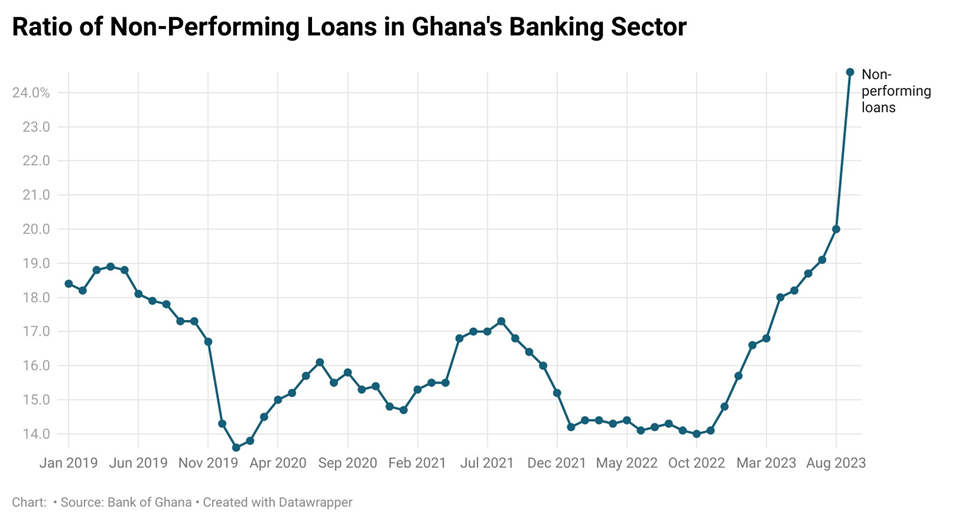

Another significant area of concern is the surge in Non-Performing Loans (NPL) ratios from 15.3% to 24.6%, triggering a crisis in the banking sector. Laeven and Valencia (2018) contend that any developing or emerging economy with an NPL ratio exceeding 20% is deemed to be in crisis.

The increased prevalence of non-performing loans has contributed to the reduction in credit extended to the private sector. Banks have been cautious in providing credit to private entities but have shown a preference for lending to the government, attracted by the lucrative opportunities presented by government short-term papers.

Ghana’s economic difficulties extend beyond mere monetary policy adjustments, delving into substantial fiscal challenges. While the Central Bank focuses on curbing inflationary tendencies and stabilizing the depreciating cedi, the central government consistently taps into the treasury bill market to secure substantial funds weekly, primarily to finance its ongoing expenditures.

This is facilitated by the elevated treasury bill rates set by the central bank. Consequently, maintaining a high Cash Reserve Ratio under these circumstances could potentially exacerbate rather than alleviate the situation. Commercial banks, still grappling with the aftermath of the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme that left many on the brink of insolvency, are particularly vulnerable to such monetary policies.

If the central bank decides to maintain the increase in the Cash Reserve Ratio from 15.3% to 24%, there’s a high probability of another banking sector crisis emerging in the medium and long term. This situation could ultimately result in the collapse, merger, and acquisition of commercial banks as a measure to safeguard depositors’ funds.

BACKGROUND

According to Bawumia (2010), the Bank of Ghana’s approach to managing inflation within the framework of indirect monetary instruments was grounded in the monetarist perspective, which posits that inflation primarily stems from monetary factors. This implies that effective management involves regulating the expansion of the money supply in the economy.

Consequently, the Bank of Ghana (BoG) employs indirect monetary tools such as reserve requirements, open market operations, repurchase agreements (Repos), and rediscount facilities. These measures mandate Ghanaian banks to set aside a defined portion of their deposits as reserves held at the central bank.

Ghana has had a long history of using reserve requirements for both prudential and monetary management purposes (Bawumia, 2010). Within the Bank of Ghana’s monetary policy operational framework, primary/ cash reserve requirements have a role in helping with prudential and liquidity management. Primary/Cash Reserve Requirements aim not only at contributing to the sterilization of commercial bank reserves but also at keeping liquidity buffers for financial stability reasons.

Concerning the reserve requirement system, the Bank of Ghana mandates commercial banks to hold a certain ratio of their liabilities subject to reserve requirements in their accounts with the central bank. The reserve requirement ratio of total deposits (domestic and foreign) currently stands at 15 percent since November 2023 and is mandatorily held in domestic currency. The reserve ratio is calculated as the simple average of all deposits (including demand, time, savings, and foreign currency deposits) and has a maintenance period of one week.

The reserves are currently unremunerated and unavailable to commercial banks for lending. The Primary/ Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) is a major component of the BoG’s monetary policy. The central bank uses this percentage to regulate the cash flow, money supply, inflation level, and liquidity in the economy. When the CRR increases, the liquidity reduces with the banks, and vice versa. During high inflation, the Bank of Ghana tries to reduce cash flow in the economy by increasing the current Cash Reserve Ratio based on the Bank’s loan-to-deposit ratio.

Consequently, it reduces the amount of loans banks can lend to borrowers. Investments slow down in the economy, and finally, the cash flow minimizes, negatively impacting the country’s economic growth. However, it also helps to bring down the inflation levels. Conversely, when the inflation levels are low, the BoG pumps up funds into the economy by lowering the CRR rate to increase the amount available for lending with the banks. As a result, banks sanction a larger number of loans at cheaper interest rates, increasing the overall money supply in the economy. It ultimately boosts the economic growth rate of the country.

Bawumia (2010) posited that the level of the primary /cash reserve ratio has fluctuated over the years reflecting liquidity conditions in the banking sector, reaching its highest level of 27% in 1990, and after 1990 the ratio was progressively lowered until it reached as lowest point of 5% in 1993. The primary /cash reserve ratio was again raised to 10% in 1996 and then lowered to 8% in 1997 when foreign currency deposits were included in the total deposits for calculation of the primary/cash reserve ratios.

In 2000 in response to rising inflation and sharp depreciation of the cedi, the primary/cash reserve ratio was increased to 9% (Yahya, 2001). In 2005, the Bank of Ghana announced major changes in the primary /cash reserve ratio of 9% and in addition, banks were expected to secondary reserve ratio of 35%. At that time commercial banks were required to keep 9% of their eligible deposits as primary/cash reserve ratio at the central bank.

In addition, banks were required also to let go of 35% of their eligible deposits as secondary reserves in the form of treasury bills and medium-term government securities. Bawumia (2010) argued then that the high level of reserve requirements was a legacy of high fiscal deficits and the need for the government to have a captive market to finance these deficits. In 2006, the Bank of Ghana continued with 9% primary /cash reserve ratios for the banks but reduced the secondary reserve ratio from 35% to 15% which was later abolished that same year.

2024 OUTLOOK: IMPACT OF THE NEW HIGHER CASH RESERVE RATIOS ON BANKS

Bank of Ghana MPC’s recent adjustment for the existing Cash Reserve Ratio of 15% with a now graduated ratio based on the existing Loan to the loan-to-deposit ratio:

i. Banks with a Loan to Deposit ratio above 55 percent will have to meet a CRR of 15 percent. ii. Banks with a Loan to Deposit ratio between 40 percent to 55 percent will have to meet a CRR of 20 percent.

iii. Banks with Loan to Deposit ratios below 40 percent will be required to hold a CRR of 25 percent.

From theoretical evidence, the Bank of Ghana introduced the new cash reserve ratios to curtail the rising inflation and persistent depreciation of the cedi since the beginning of the year 2024. The Bank of Ghana with the new and higher cash reserve ratios were intended to assist in a disinflation process as well as slow down the persistent depreciation of the local currency however, Bawumia’s 2010 argues that the high-level cash reserve requirements could be the legacy of high fiscal deficits and the high level of primary/cash reserve requirements could also be a captive market to finance these deficits.

GHANA’S OVERBURDENED TREASURY BILL MARKET

Maintaining a high Cash Reserve Ratio would have been advisable and impactful if the government retained access to both the domestic and international bond markets. However, the government’s current lack of access to these liquidity markets has forced it to rely solely on generating cash from the treasury bill space. This dependency has led to the need for very high interest rates to entice commercial banks and private investors to participate.

In 2024, the Ghanaian government has outlined its plan to address a cash deficit of GHS 62.6 billion through a combination of foreign and domestic financing sources. The foreign financing component is set to reach GHS464 million (1.6% of GDP) on a net basis. This foreign financing will encompass funds from the IMF’s Extended Credit Facility (ECF) program disbursements amounting to US$ 720 million and World Bank Development Policy Operation (DPO) funding of US$ 300 million.

The remaining net domestic financing is anticipated to total GHS 61.4 billion (5.8% of GDP), constituting 99.3% of the overall financing for 2024. This domestic financing will primarily stem from debt issuances in the short-term domestic market. The government has clarified that Treasury bills (T-bills) were not included in the Debt and Debt Exchange Program (DDEP), indicating an active and functional Treasury market throughout 2024 and the medium-term.

Given the challenges related to issuing medium-term bonds, the domestic financing strategy emphasizes continuous T-bill issuances to support the 2024 budget. Additionally, apart from the planned net domestic financing, the strategy aims to build cash reserves for debt operations and effective cash management. It also includes plans for the issuance or reopening of newly exchanged bonds and the repayment of holdout bonds.

Moreover, the domestic financing strategy proposes the issuance of government securities to address the recapitalization costs of commercial banks resulting from the DDEP within the financial sector.

CONSEQUENCES AND OUTCOME

Another area of concern about the higher cash reserve requirements is that these higher ratios could affect the credit to the private sector. According to the BoG March 2024 MPC report, private sector credit growth by banks remained sluggish, with February 2024 showing a 5.1 percent increase compared to 29.5 percent growth in February 2023. Conversely, investments by banks in Government of Ghana (GOG) and Bank of Ghana (BOG) instruments surged to GHS 53.6 billion, marking a 67.6 percent year-on-year rise, contrasting with a 36.9 percent increase in the corresponding period of 2023. Adjusted for inflation, private sector credit saw a decline of 14.7 percent, compared to a 15.3 percent contraction in February 2023. BoG attributed the sluggishness to the risk aversion of banks as asset quality weakened over the period.

Declined was not the making of banks but harsh economic conditions of higher inflation, persistent depreciation of the Cedi, myriad of higher and nuisance taxes and higher utilities and energy crises as well as higher policy rates which made the banks adopt lazy banking by investing in the money market instruments. Government after the Domestic Exchange Programme (DDEP) in 2023, Treasury bill instruments became a lucrative business for banks as rates rose above 30 percent.

The Bank of Ghana’s policy on the New Cash Reserve Ratios has a notable flaw in that it overlooks the GHS 50.6 billion worth of government bonds that were previously restructured during DDEP. These bonds constitute part of the commercial banks’ total deposits of GHC 224 billion, with customers’ deposits being utilized for purchasing these government bonds. Consequently, the Bank of Ghana should have considered the GHS 50.6 billion of bonds that were restructured before implementing the new, higher Cash Reserve Ratios; otherwise, it amounts to double accounting.

The government bonds have a final maturity period in 2031, and many bank boards and management teams are concerned that this new directive could lead to a depletion of their resources soon as many banks may not be liquid enough to operate. The central question remains: How did the Bank of Ghana establish the new Cash Reserve Ratio without factoring in the restructured bonds held by commercial banks, primarily funded by depositors’ money? Besides Bawumia (2010) argued that the high level of reserve requirements was a legacy of high fiscal deficits so why the heavy dependence on monetary policy to solve a problem deeply rooted in fiscal recklessness?

Another significant area of concern is the surge in Non-Performing Loans (NPL) ratios from 15.3% to 24%, triggering a crisis in the banking sector. Laeven and Valencia (2018) contend that any developing or emerging economy with an NPL ratio exceeding 20% is deemed to be in crisis. The increased prevalence of non-performing loans has contributed to the reduction in credit extended to the private sector. Banks have been cautious in providing credit to private entities but have shown a preference for lending to the government, attracted by the lucrative opportunities presented by government short-term papers.

Ghana’s economic difficulties extend beyond mere monetary policy adjustments, delving into substantial fiscal challenges. While the Central Bank focuses on curbing inflationary tendencies and stabilizing the depreciating cedi, the central government consistently taps into the treasury bill market to secure substantial funds weekly, primarily to finance its ongoing expenditures.

This is facilitated by the elevated treasury bill rates set by the central bank. Consequently, maintaining a high Cash Reserve Ratio under these circumstances could potentially exacerbate rather than alleviate the situation. Commercial banks, still grappling with the aftermath of the Domestic Debt Exchange Programme that left many on the brink of insolvency, are particularly vulnerable to such monetary policies.

If the central bank decides to maintain the increase in the Cash Reserve Ratio, there’s a high probability of another banking sector crisis emerging in the medium and long term. This situation could ultimately result in the collapse, merger, and acquisition of commercial banks as a measure to safeguard depositors’ funds.

RECOMMENDATION

While it can be beneficial for central banks to implement higher Cash/Primary Reserve ratios to control inflation and stabilize the local currency’s value, excessive ratios can lead commercial banks to hold more cash with the central bank, thereby limiting their ability to lend. Conversely, lower cash reserve ratios allow banks to maintain less cash with the central bank, boosting their lending capacity.

Bank of Ghana should reconsider reducing the mammoth cash reserve ratios by taking into account the GHS50.6 billion of customers’ deposits used to purchase restructured government bonds with an extended maturity period until 2031.

Furthermore, the Bank of Ghana and commercial banks need to exert significant effort to reduce the current Non-Performing Loan (NPL) ratio from 24% to around 10% to fortify the banking sector’s resilience. A resilient banking sector encompasses more than just profitability; high NPLs can lead to poor capitalization among banks, liquidity challenges, and even insolvency for some institutions. The Bank of Ghana’s MPC report in March 2024 affirmed these concerns, indicating a mixed outlook on key financial soundness indicators.

Over the past two years, the private sector has suffered due to the government’s overwhelming presence in the treasury bill market. To revitalize the private sector, authorities must focus on lowering short-term bill rates below 20 percent to foster competitiveness in the domestic market. Additionally, efforts should be made to curb the increasing diversion of credit from the private sector to the central government.

Addressing Ghana’s economic challenges requires a comprehensive approach that goes beyond relying solely on traditional monetary policy tools like increasing commercial banks’ reserve requirements or adjusting monetary policy rates. These measures have been excessively utilized in previous years and have become less effective due to the structure of the Ghanaian economy, which has developed a level of resistance to them over time. Bawumia (2010) affirms that the high level of reserve requirements (monetary policy instrument) reflects a legacy of high fiscal deficits.

In addition to monetary policy adjustments, significant fiscal interventions are necessary to navigate the economic difficulties. This includes implementing substantial reductions in government expenditure to alleviate the current economic strain. To combat inflationary pressures effectively, authorities must proactively reduce central government spending by an additional 30%, with a particular focus on trimming down flagship programs that have failed to deliver significant economic benefits since their inception.

In summary, the government should refrain from burdening the banks and instead concentrate on making drastic cuts to its excessively large budget. Commercial banks have incurred considerable losses as a result of the DDEP and are still in the process of recuperating; they should be allowed to fully recover without further burdens!