Why Nigeria’s Job Market Isn’t Keeping Up With Economic Growth

Nigeria’s economic growth is often celebrated, but a critical issue lies hidden beneath the surface: this growth has not been matched by proportional increases in formal wage jobs.

As Ndiame Diop, the World Bank Country Director for Nigeria, points out, African economies—including Nigeria—generate fewer formal wage jobs from economic growth than many other regions in the world. This reality underlines a significant barrier to economic inclusion and highlights why economic progress alone doesn’t guarantee social prosperity.

“These workers, the so-called “working poor,” operate in an environment that doesn’t provide the stability or resources needed to break free from poverty.”

Tayo Aduloju, CEO of the Nigeria Economic Summit Group (NESG), echoes this sentiment. He emphasises that “growth without integrating digital transformation into the financial system risks leaving a substantial part of the population behind.” He recounts how, during Nigeria’s rapid economic expansion in the 2000s, much of the growth was “jobless,” benefiting a small sector of the population while failing to create enough stable, formal wage jobs.

Between 1991 and 2016, Nigeria’s job elasticity—a measure of how job creation responds to economic growth—was about 0.6. In real terms, this means that for every 10 jobs created, only six people were lifted out of poverty, with the remaining four continuing to struggle.

These workers, the so-called “working poor,” operate in an environment that doesn’t provide the stability or resources needed to break free from poverty.

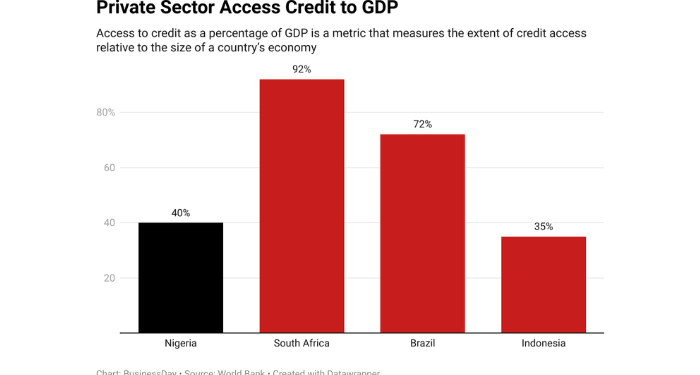

Aduloju asserts that addressing this gap will require comprehensive access to finance, markets, skills, and job training. Diop further identifies two key paths for Nigeria: fostering the growth of labour-intensive, export-oriented sectors and supporting the growth of micro and small enterprises with financing to scale to medium-sized firms.

These firms, if given the resources to scale, could help drive more inclusive employment opportunities, extending the benefits of economic growth to more Nigerians.

Olayemi Cardoso, the Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), also weighed in on the impact of financial inclusion, emphasising that “financial inclusion is not just about banking—it’s a pillar of economic growth.”

The CBN recently raised the minimum capital requirement for banks to promote greater stability and allow banks to take more risks, give more loans, and provide financial products to MSMEs, investing in the technology necessary to expand financial services to underserved populations. Cardoso views financial inclusion as key to poverty reduction, reducing income inequality, and boosting productivity.

A vital element in driving financial inclusion and job creation is Nigeria’s fintech sector, which provides digital financial solutions that enable millions of unbanked Nigerians to access financial services. One of the major barriers to Nigerian fintech is regulatory challenges.

Babajide Sanwo-Olu, Governor of Lagos State, represented by his deputy Kadiri Hamzat, acknowledges fintech as critical to creating seamless payment solutions and financial access. “We need to drive fintech growth and remove barriers to financial services,” he asserts.

Lagos has established the Lagos State Science, Research, and Innovation Council (LASRIC) to foster fintech and innovation, signalling a commitment to advancing digital & financial inclusion and technology at large. This underscores the role of states as enablers and drivers of the economy.

Economic liberalisation, however, should not be mistaken as merely a “capitalist” agenda. It’s about empowering citizens to achieve shared prosperity by devolving economic power and creating pathways for productivity and upward mobility.

Yet, some states are veering toward an outdated model of state ownership. Recently, the Benue Investment and Property Company (BIPC) announced plans to take over the Ben Fruits Company Limited to revive juice production.

This approach is reminiscent of the past, when the government owned and managed various enterprises—a model that often stifles growth and innovation. Ben Fruits was previously government-owned, but after its acquisition by Teragro Commodities in 2011, it has remained dormant since 2015.

Reflecting on Nigeria’s post-independence trajectory with BusinessDay, Sam Ohuabunwa, a member of Vision 2010, once noted that centralisation took hold after 1966, with the government monopolising control over schools, hospitals, and industries. “If those in power had the choice, they would have made churches and mosques government-owned too,” he added.

His words highlight the perils of excessive government control—a lesson that must guide Nigeria’s approach to shared prosperity even as the country is making efforts to bounce back from the current economic woes.

A recurring theme among experts is partnership. This partnership should not be limited to financial services providers alone but to the states.

States should welcome private investors, while locals should be educated on respecting private capital’s role in local economies.

Barth Nnaji, founder of Geometric Power, underscores the importance of transparency on the ease of doing business, noting that “if you’re serious about ease of doing business, you outline what you will do for investors and follow through. There’s no room for bribes.”

Financial inclusion, therefore, cannot succeed in isolation. It requires collaboration between private enterprises, government agencies, and local communities to make Nigeria’s economic growth inclusive and sustainable. With the right partnerships and policies, Nigeria can ensure that growth goes beyond figures and truly improves the lives of its people.