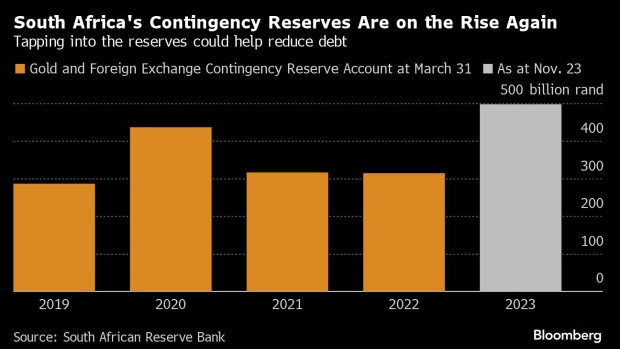

Should South Africa tap $26 billion in paper profits?

With South Africa’s options running out to fund a widening budget deficit and contain runaway debt, the government is considering tapping for the first time billions of dollars of paper profits earned from its reserves — an amount equivalent to some 7% of the country’s economy. Held in an account administered by the central bank on behalf of the Treasury, it represents the difference between the current value of the assets and the price at which they were purchased. Realizing any gains would require selling part or all of the underlying assets, a move that could rattle investors — depending on how it’s done.

1. How does the contingency reserve account work?

The Gold & Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account contains the unrealized profits or losses on the central bank’s stock of gold, foreign exchange, and forwards or swaps agreements. The balance can fluctuate widely, depending on how those assets perform and only reflects movements on paper. By way of example, if the government bought $1 billion of gold and the value moved up to $1.5 billion, the $500 million gain would be reflected in the contingency account, and a third of the total holding would have to be sold to access it.

2. How much money does the South African government want to access?

In December 2023, the Treasury said it’s considering withdrawing as much as half of the 497 billion rand ($26 billion) in the reserve account. No final decision has been taken. RMB Morgan Stanley Economist Andrea Masia expects an initial transfer of as much as 100 billion rand to be made once the details of the governing framework are finalized some time in 2024.

3. Would that be a good idea?

It depends on the mechanics. The GFECRA, in conjunction with the country’s foreign reserves, can be utilized to maintain liquidity in an economic crisis and meet the country’s international financial obligations such as settling debt denominated in foreign currency, paying for imports and absorbing sudden capital movements. If a portion of the money is withdrawn over an extended period subject to strict terms and conditions and is put to good use — such as reducing the budget deficit or debt — it may be viewed positively. But problems could arise if the account is drained or the central bank is asked to print the money and hand it over to the Treasury. Central bank Governor Lesetja Kganyago has warned that investors may be sent “running for the hills” if they doubt the country is able to meet its obligations. There would also be a risk of a run on the rand. Some investors say that tapping the contingency account may prove to be beneficial because an influx of cash would reduce the amount the government would need to raise to fund the budget deficit and that would have a positive spinoff on its borrowing costs.

4. Where does the process stand?

The Treasury and central bank have been engaged since 2023 about how best to utilize the funds, discussing how much should be withdrawn and over how long, and what costs will be involved. International experts have been engaged to advise them. In January, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana said an agreement had yet to reached and there was no pressure to arrive at one. Tapping the contingency reserves “is a difficult issue because it also raises challenges about its impact on the balance sheet of the central bank,” he said. “There’s been reluctance, even on our side, to take that route.”

5. What happens in other countries?

A number of nations’ central banks that hold mostly foreign-exchange assets on their balance sheets, including those in Switzerland, Chile and Poland, periodically transfer some or all of the gains made from valuation adjustments to the government, according to a draft research paper by Amia Capital LLP economists Pedro Maia and Annik Ketterle, and Guido Maia, a London School of Economics PhD candidate. The frequency and mechanism through which transfers take place differ depending on national legislation, they said.